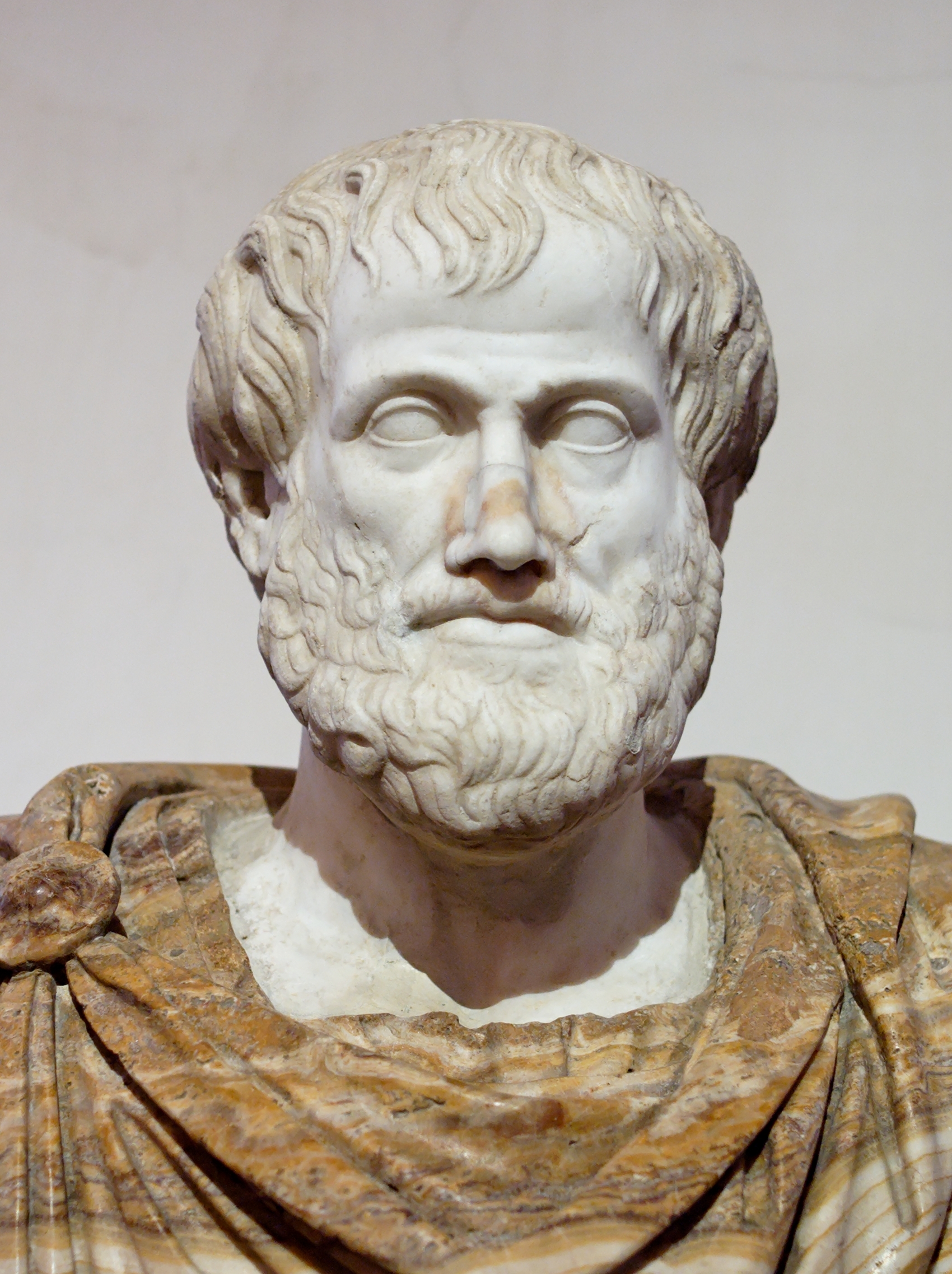

La définition fameuse de la tragédie par Aristote, exposant la notion de catharsis.

Poétique

Aristote citations célèbres

Citations sur les hommes et les garçons de Aristote

Politique

Aristote Citations

Éthique à Nicomaque

Métaphysique

Organon, V - Topiques

Organon, V - Topiques

Définitions du citoyen et de la cité.

Politique

Politique

“Le bonheur, avons-nous dit, est une certaine activité de l’âme conforme à la vertu.”

Éthique à Nicomaque

La Politique

Aristote: Citations en anglais

Book I, 1369a.5

Rhetoric

Variante: All human actions have one or more of these seven causes: chance, nature, compulsions, habit, reason, passion and desire

Source: Selected Works

“It is not always the same thing to be a good man and a good citizen.”

Source: Selected Writings From The Nicomachean Ethics And Politics

“Misfortune shows those who are not really friends.”

Eudemian Ethics, Book VII, 1238a.20

Eudemian Ethics

Variante: A friend to all is a friend to none.

“Happiness depends upon ourselves”

An interpretative gloss of Aristotle's position in Nicomachean Ethics book 1 section 9, tacitly inserted by J. A. K. Thomson in his English translation The Ethics of Aristotle (1955). The original Greek at Book I 1099b.29 http://perseus.uchicago.edu/perseus-cgi/citequery3.pl?dbname=GreekFeb2011&getid=0&query=Arist.%20Eth.%20Nic.%201099b.25, reads ὁμολογούμενα δὲ ταῦτ’ ἂν εἴη καὶ τοῖς ἐν ἀρχῇ, which W. D. Ross translates fairly literally as [a]nd this will be found to agree with what we said at the outset. Thomson's much freer translation renders the same passage thus: [t]he conclusion that happiness depends upon ourselves is in harmony with what I said in the first of these lectures; the words "that happiness depends upon ourselves" were added by Thomson to clarify what "the conclusion" is, but they do not appear in the original Greek of Aristotle. Rackham's earlier English translation added a similar gloss, but averted confusion by confining it to a footnote.

Disputed

Variante: Happiness depends upon ourselves

Source: See http://www.mikrosapoplous.gr/aristotle/nicom1b.htm#I9 for the original Greek and Ross's translation; Thomson's translation can be viewed on Google Books https://books.google.com/books?id=9SFrNWmO654C&dq=%22happiness+depends+upon+ourselves%22+aristotle&focus=searchwithinvolume&q=%22happiness+depends+upon+ourselves%22+.

Source: Rackham's translation of this passage is available here http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0054%3Abook%3D1%3Achapter%3D9%3Asection%3D8

“Poverty is the parent of revolution and crime.”

Book II, Section VI ( translation http://archive.org/stream/aristotlespolit00aris#page/69/mode/1up by Benjamin Jowett)

Politics

Contexte: One would have thought that it was even more necessary to limit population than property; and that the limit should be fixed by calculating the chances of mortality in the children, and of sterility in married persons. The neglect of this subject, which in existing states is so common, is a never-failing cause of poverty among the citizens; and poverty is the parent of revolution and crime.

Source: Will Durant, The Story of Philosophy: The Lives and Opinions of the World's Greatest PHilosophers (1926), reprinted in Simon & Schuster/Pocket Books, 1991, ISBN 0-671-73916-6], Ch. II: Aristotle and Greek Science; part VI: Psychology and the Nature of Art: "Artistic creation, says Aristotle, springs from the formative impulse and the craving for emotional expression. Essentially the form of art is an imitation of reality; it holds the mirror up to nature. There is in man a pleasure in imitation, apparently missing in lower animals. Yet the aim of art is to represent not the outward appearance of things, but their inward significance; for this, and not the external mannerism and detail, is their reality.

Book VIII 1337b.5 http://books.google.com/books?id=ZrDWAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA245&dq=%22absorb+and+degrade+the+mind%22&hl=en&sa=X&ei=c6NaUbatEYWp4AOWp4CoBA&ved=0CHYQ6AEwDA#v=onepage&q=%22absorb%20and%20degrade%20the%20mind%22&f=false, 1885 edition

Politics

Contexte: There can be no doubt that children should be taught those useful things which are really necessary, but not all things, for occupations are divided into liberal and illiberal; and to young children should be imparted only such kinds of knowledge as will be useful to them without vulgarizing them. And any occupation, art, or science which makes the body, or soul, or mind of the freeman less fit for the practice or exercise of virtue is vulgar; wherefore we call those arts vulgar which tend to deform the body, and likewise all paid employments, for they absorb and degrade the mind. There are also some liberal arts quite proper for a freeman to acquire, but only in a certain degree, and if he attend to them too closely, in order to attain perfection in them, the same evil effects will follow.

“Money was intended to be used in exchange, but not to increase at interest.”

Book I, 1258b.4

Politics

Contexte: Money was intended to be used in exchange, but not to increase at interest. And this term interest, which means the birth of money from money, is applied to the breeding of money because the offspring resembles the parent. Wherefore of all modes of getting wealth this is the most unnatural.

Book I, 1098a-b; §7 as translated by W. D. Ross

Nicomachean Ethics

Contexte: Let this serve as an outline of the good; for we must presumably first sketch it roughly, and then later fill in the details. But it would seem that any one is capable of carrying on and articulating what has once been well outlined, and that time is a good discoverer or partner in such a work; to which facts the advances of the arts are due; for any one can add what is lacking. And we must also remember what has been said before, and not look for precision in all things alike, but in each class of things such precision as accords with the subject-matter, and so much as is appropriate to the inquiry. For a carpenter and a geometer investigate the right angle in different ways; the former does so in so far as the right angle is useful for his work, while the latter inquires what it is or what sort of thing it is; for he is a spectator of the truth. We must act in the same way, then, in all other matters as well, that our main task may not be subordinated to minor questions. Nor must we demand the cause in all matters alike; it is enough in some cases that the fact be well established, as in the case of the first principles; the fact is the primary thing or first principle. Now of first principles we see some by induction, some by perception, some by a certain habituation, and others too in other ways. But each set of principles we must try to investigate in the natural way, and we must take pains to state them definitely, since they have a great influence on what follows. For the beginning is thought to be more than half of the whole, and many of the questions we ask are cleared up by it.

The Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers