But the peculiar evil of silencing the expression of an opinion is, that it is robbing the human race; posterity as well as the existing generation; those who dissent from the opinion, still more than those who hold it. If the opinion is right, they are deprived of the opportunity of exchanging error for truth: if wrong, they lose, what is almost as great a benefit, the clearer perception and livelier impression of truth, produced by its collision with error.

en

De la liberté

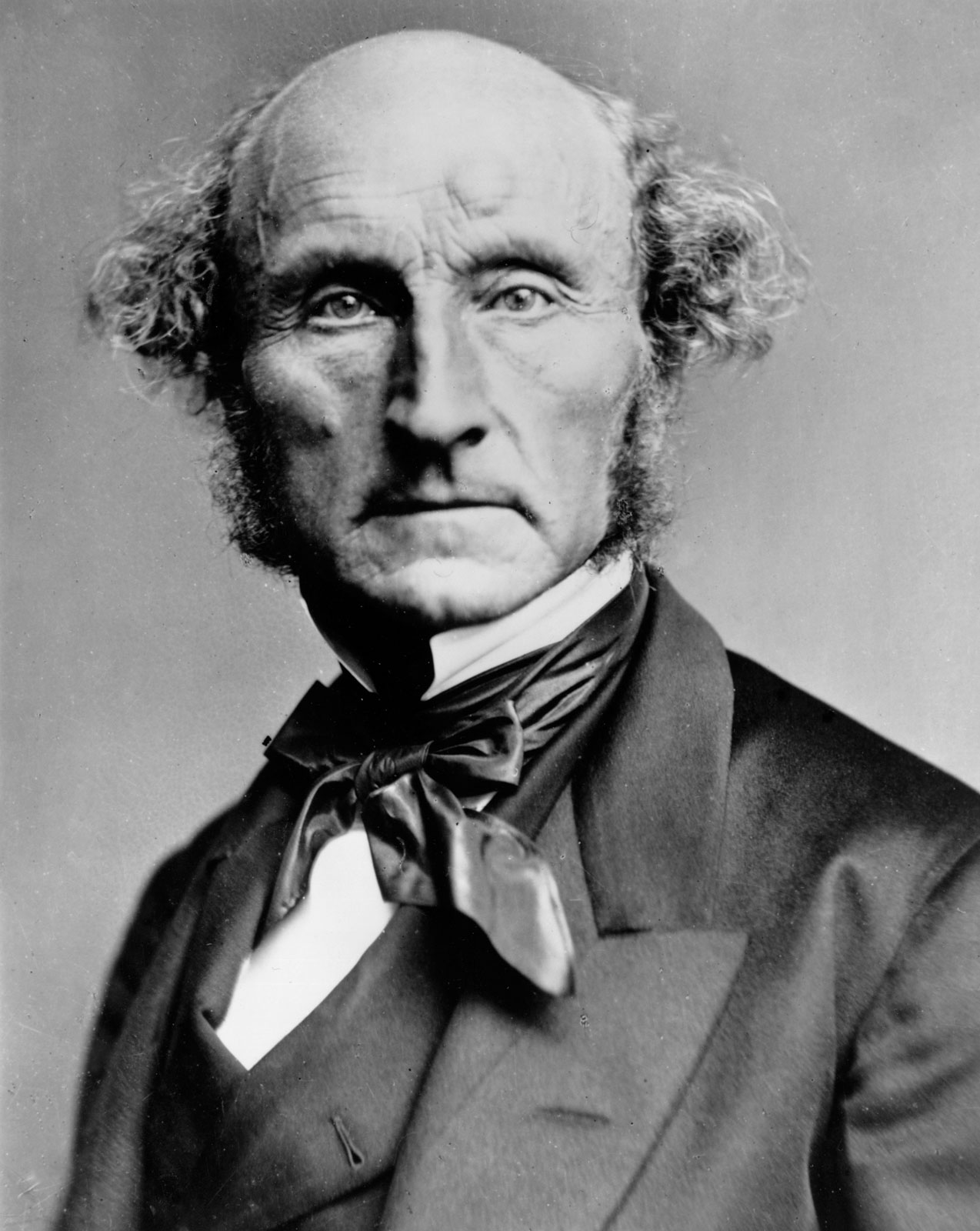

John Stuart Mill citations célèbres

“Celui qui ne connaît que ses propres arguments connaît mal sa cause.”

He who knows only his own side of the case, knows little of that.

en

De la liberté

“L'utilité même d'une opinion est affaire d'opinion.”

The usefulness of an opinion is itself matter of opinion.

en

De la liberté

History teems with instances of truth put down by persecution. If not suppressed forever, it may be thrown back for centuries.

en

De la liberté

“Le génie ne peut respirer librement que dans une atmosphère de liberté.”

Genius can only breathe freely in an atmosphere of freedom.

en

De la liberté

That so few now dare to be eccentric, marks the chief danger of the time.

en

De la liberté

Citations sur les hommes et les garçons de John Stuart Mill

That principle is, that the sole end for which mankind are warranted, individually or collectively, in interfering with the liberty of action of any of their number, is self-protection. That the only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others.

en

De la liberté

The worth of a State, in the long run, is the worth of the individuals composing it; and a State which postpones the interests of their mental expansion and elevation, to a little more of administrative skill, or that semblance of it which practice gives, in the details of business; a State, which dwarfs its men, in order that they may be more docile instruments in its hands even for beneficial purposes, will find that with small men no great thing can really be accomplished; and that the perfection of machinery to which it has sacrificed everything, will in the end avail it nothing, for want of the vital power which, in order that the machine might work more smoothly, it has preferred to banish.

en

De la liberté

His own good, either physical or moral, is not a sufficient warrant. He cannot rightfully be compelled to do or forbear because it will be better for him to do so, because it will make him happier, because, in the opinions of others, to do so would be wise, or even right.

en

De la liberté

John Stuart Mill: Citations en anglais

Source: On Representative Government (1861), Ch. VII: Of True and False Democracy; Representation of All, and Representation of the Majority only (p. 248)

Principles of Political Economy http://www.econlib.org/library/Mill/mlP64.html (1848), Book V, Chapter II

On Representative Government (1861)

Source: Autobiography (1873)

https://archive.org/details/autobiography01mill/page/39/mode/1up pp. 39–40

Source: Autobiography (1873)

Source: https://archive.org/details/autobiography01mill/page/163/mode/1up p. 163

Autobiography (1873)

Contexte: I have already mentioned Carlyle's earlier writings as one of the channels through which I received the influences which enlarged my early narrow creed; but I do not think that those writings, by themselves, would ever have had any effect on my opinions. What truths they contained, though of the very kind which I was already receiving from other quarters, were presented in a form and vesture less suited than any other to give them access to a mind trained as mine had been. They seemed a haze of poetry and German metaphysics, in which almost the only clear thing was a strong animosity to most of the opinions which were the basis of my mode of thought; religious scepticism, utilitarianism, the doctrine of circumstances, and the attaching any importance to democracy, logic, or political economy. Instead of my having been taught anything, in the first instance, by Carlyle, it was only in proportion as I came to see the same truths through media more suited to my mental constitution, that I recognized them in his writings. Then, indeed, the wonderful power with which he put them forth made a deep impression upon me, and I was during a long period one of his most fervent admirers; but the good his writings did me, was not as philosophy to instruct, but as poetry to animate. Even at the time when out acquaintance commenced, I was not sufficiently advanced in my new modes of thought, to appreciate him fully; a proof of which is, that on his showing me the manuscript of Sartor Resartus, his best and greatest work, which he had just then finished, I made little of it; though when it came out about two years afterwards in Fraser's Magazine I read it with enthusiastic admiration and the keenest delight. I did not seek and cultivate Carlyle less on account of the fundamental differences in our philosophy. He soon found out that I was not "another mystic," and when for the sake of my own integrity I wrote to him a distinct profession of all those of my opinions which I knew he most disliked, he replied that the chief difference between us was that I "was as yet consciously nothing of a mystic." I do not know at what period he gave up the expectation that I was destined to become one; but though both his and my opinions underwent in subsequent years considerable changes, we never approached much nearer to each other's modes of thought than we were in the first years of our acquaintance. I did not, however, deem myself a competent judge of Carlyle. I felt that he was a poet, and that I was not; that he was a man of intuition, which I was not; and that as such, he not only saw many things long before me, which I could only when they were pointed out to me, hobble after and prove, but that it was highly probable he could see many things which were not visible to me even after they were pointed out. I knew that I could not see round him, and could never be certain that I saw over him; and I never presumed to judge him with any definiteness, until he was interpreted to me by one greatly the superior of us both -- who was more a poet than he, and more a thinker than I -- whose own mind and nature included his, and infinitely more.

Source: Autobiography (1873), Ch. 2: Moral Influences in Early Youth. My Father's Character and Opinions.

https://archive.org/details/autobiography01mill/page/45/mode/1up p. 45

Source: The enjoyments of life (such was now my theory) are sufficient to make it a pleasant thing, when they are taken en passant, without being made a principal object. Once make them so, and they are immediately felt to be insufficient. They will not bear a scrutinizing examination. Ask yourself whether you are happy, and you cease to be so. The only chance is to treat, not happiness, but some end external to it, as the purpose of life. Let your self-consciousness, your scrutiny, your self-interrogation, exhaust themselves on that; and if otherwise fortunately circumstanced you will inhale happiness with the air you breathe, without dwelling on it or thinking about it, without either forestalling it in imagination, or putting it to flight by fatal questioning. This theory now became the basis of my philosophy of life. And I still hold to it as the best theory for all those who have but a moderate degree of sensibility and of capacity for enjoyment; that is, for the great majority of mankind."

Autobiography, Ch 5, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/10378/10378-h/10378-h.htm#link2H_NOTE https://www.laits.utexas.edu/poltheory/mill/auto/auto.c05.html source: Autobiography (1873), Ch. 5: A Crisis in My Mental History (p. 100)

Source: Autobiography (1873)

Source: https://archive.org/details/autobiography01mill/page/184/mode/1up p. 184

“France has done more for even English history than England has.”

John Stuart Mill. Michelet.On the writing of English history. Complete Works Vol 20. Page 221.http://files.libertyfund.org/pll/pdf/Mill_0223-20_EBk_v7.0.pdf

Note to Analysis of the Phenomena of the Human Mind http://books.google.com/books?id=GxIuAAAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=james+mill&ei=jsFoR7yAOYfQiwHEzdVv&ie=ISO-8859-1#PPA5,M1 (1829) by James Mill, edited with additional notes by John Stuart Mill (1869)

Source: Autobiography (1873)

https://archive.org/details/autobiography01mill/page/19/mode/1up p. 19

Source: https://archive.org/details/autobiography01mill/page/141/mode/1up pp. 141-142

Source: Autobiography (1873)

https://archive.org/details/autobiography01mill/page/38/mode/1up p. 38

Source: Autobiography (1873), Ch. 2: Moral Influences in Early Youth. My Father's Character and Opinions.

Source: Autobiography (1873)

https://archive.org/details/autobiography01mill/page/35/mode/1up p. 35

Source: Autobiography (1873), Ch. 1: Childhood and Early Education (pp. 13-14)

https://archive.org/details/autobiography01mill/page/19/mode/1up pp. 19-20

Source: https://archive.org/details/autobiography01mill/page/140/mode/1up pp. 140-141

Source: Autobiography (1873)

Source: https://archive.org/details/autobiography01mill/page/230/mode/1up p. 230

Source: Autobiography (1873)

https://archive.org/details/autobiography01mill/page/10/mode/1up p. 10

Source: On Liberty (1859), Ch. III: Of Individuality, As One of the Elements of Well-Being

Source: https://archive.org/details/autobiography01mill/page/55/mode/1up p. 55

Source: Autobiography (1873)

https://archive.org/details/autobiography01mill/page/42/mode/1up p. 42