“The moving power of mathematical invention is not reasoning, but imagination.”

Quoted in Robert Perceval Graves, The Life of Sir William Rowan Hamilton, Vol. 3 (1889), p. 219.

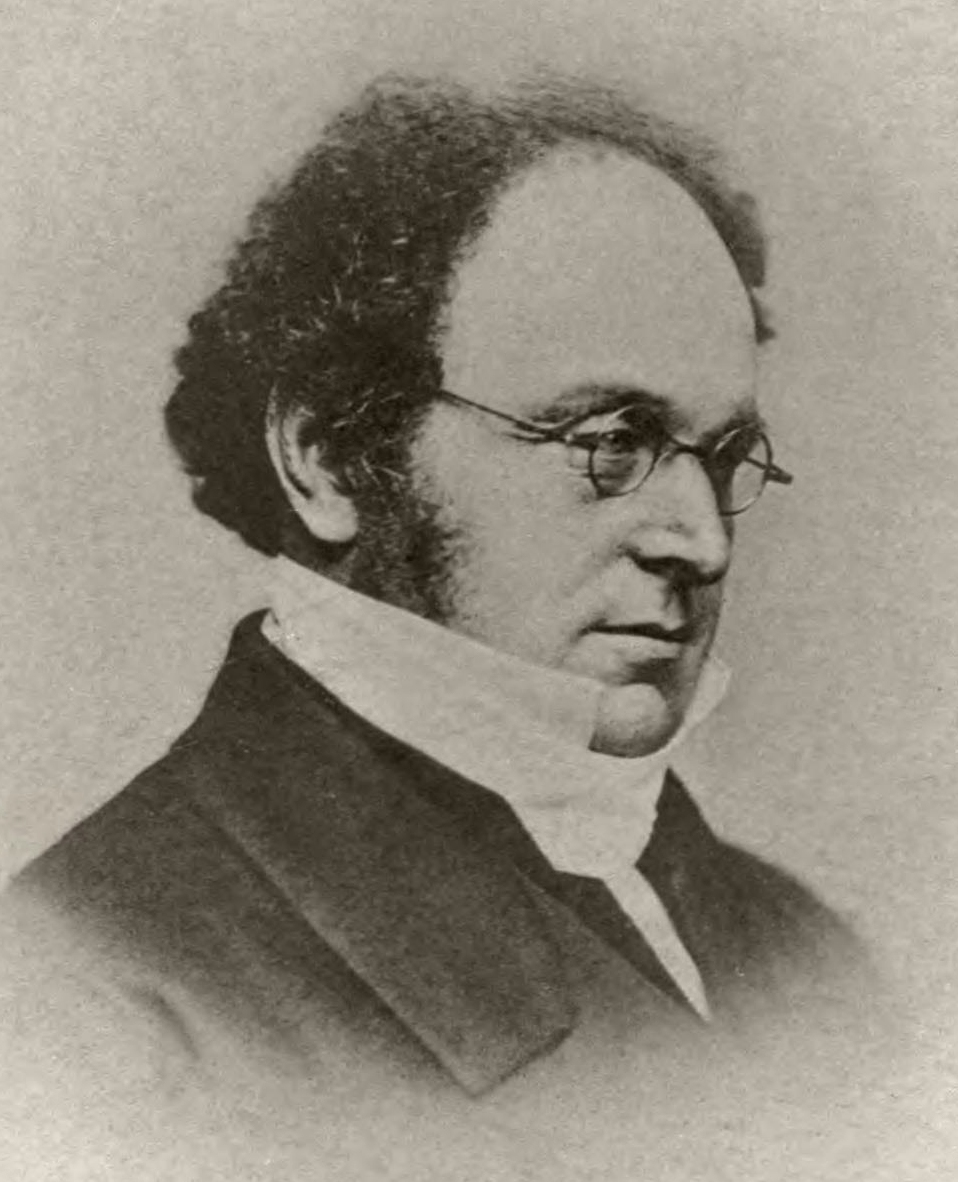

Augustus De Morgan – angielski matematyk i logik.

Studiował w Trinity College na Uniwersytecie Cambridge, które ukończył z 4. lokatą . W latach 1828–1831 i 1836–1866 był profesorem matematyki w londyńskim University College. Zajmował się głównie logiką formalną i teorią szeregów – badając sylogistykę, jako jeden z pierwszych doszedł do podstawowej problematyki algebry logiki i teorii relacji. Zwrócił uwagę na prawa nazwane później od jego nazwiska prawami De Morgana.

Wikipedia

“The moving power of mathematical invention is not reasoning, but imagination.”

Quoted in Robert Perceval Graves, The Life of Sir William Rowan Hamilton, Vol. 3 (1889), p. 219.

Advertisement, p.4

The Differential and Integral Calculus (1836)

“The work now before the reader is the most extensive which our language contains on the subject.”

Preface, p. iii

The Differential and Integral Calculus (1836)

The Differential and Integral Calculus (1836)

Źródło: On the Study and Difficulties of Mathematics (1831), Ch. I.

Introductory p.5

A Budget of Paradoxes (1872)

“I did not hear what you said, but I absolutely disagree with you.”

Attributed to Augustus De Morgan in: August Stern (1994). The Quantum Brain: Theory and Implications. North-Holland/Elsevier. p. 7

I use the word in the old sense: ...something which is apart from general opinion, either in subject-matter, method, or conclusion. ...Thus in the sixteenth century many spoke of the earth's motion as the paradox of Copernicus, who held the ingenuity of that theory in very high esteem, and some, I think, who even inclined towards it. In the seventeenth century, the depravation of meaning took place... Phillips says paradox is "a thing which seemeth strange"—here is the old meaning...—"and absurd, and is contrary to common opinion," which is an addition due to his own time.

A Budget of Paradoxes (1872)

It is also frequently said, when a quantity diminishes without limit, that it has nothing, zero or 0, for its limit: and that when it increases without limit it has infinity or ∞ or 1⁄0 for its limit.

The Differential and Integral Calculus (1836)

This was the method followed by Euclid, who, fortunately for us, never dreamed of a geometry of triangles, as distinguished from a geometry of circles, or a separate application of the arithmetics of addition and subtraction; but made one help out the other as he best could.

The Differential and Integral Calculus (1836)

The portion of the Integral Calculus, which properly belongs to any given portion of the Differential Calculus increases its power a hundred-fold...

The Differential and Integral Calculus (1836)