It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from regard to their own interest. We address ourselves, not to their humanity but to their self-love.

en

Recherche sur la nature et les causes de la richesse des nations (1776), Livre I

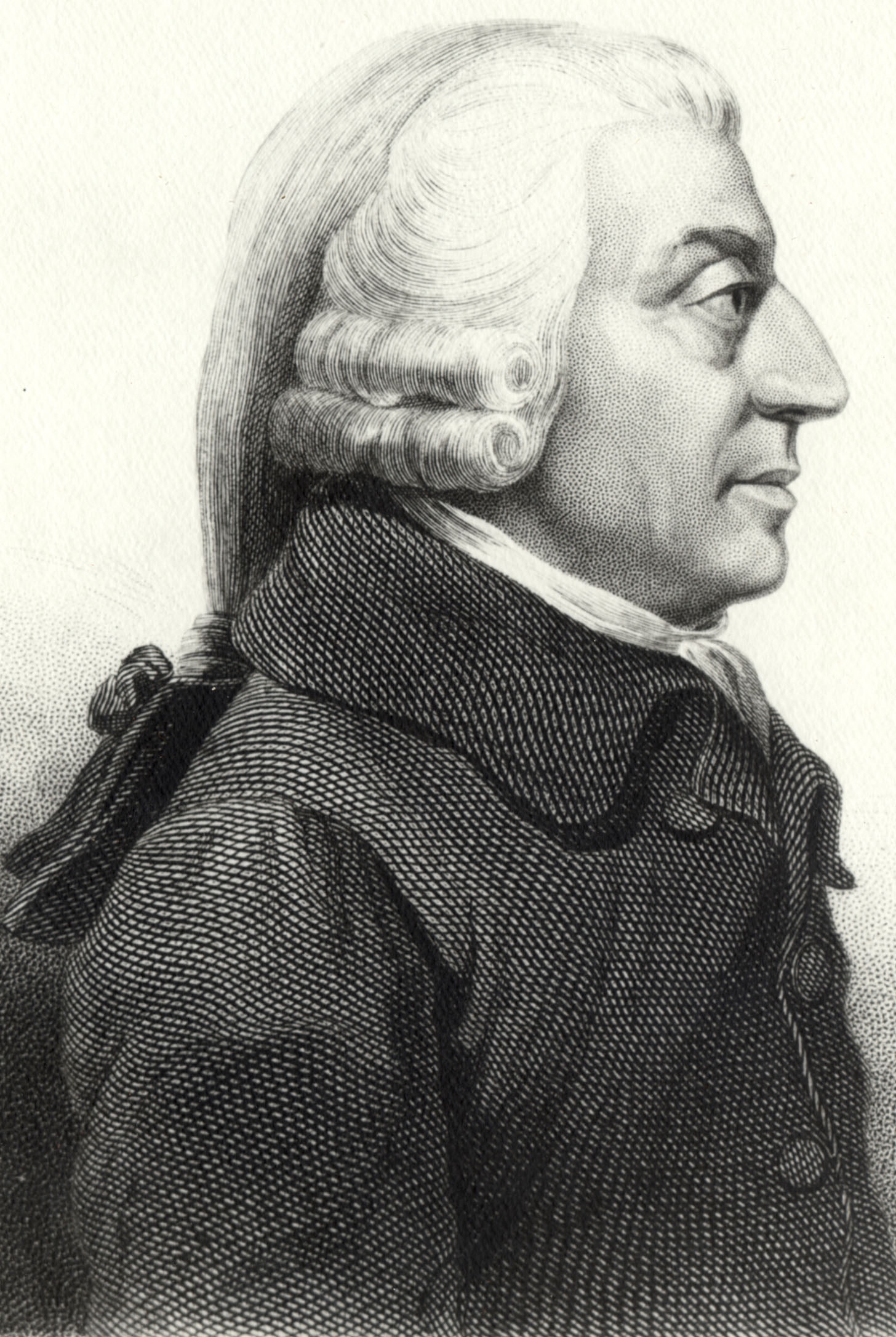

Adam Smith citations célèbres

The Wealth of Nations

en

Recherche sur la nature et les causes de la richesse des nations (1776), Livre I

en

Recherche sur la nature et les causes de la richesse des nations (1776), Livre I

en

Recherche sur la nature et les causes de la richesse des nations (1776), Livre I

Adam Smith Citations

Théorie des sentiments moraux (1759)

By preferring the support of domestic to that of foreign industry, he intends only his own security; and by directing that industry in such a manner as its produce may be of the greatest value, he intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention. Nor is it always the worse for the society that it was no part of it. By pursuing his own interest he frequently promotes that of the society more effectually than when he really intends to promote it. I have never known much good done by those who affected to trade for the public good. It is an affectation, indeed, not very common among merchants, and very few words need be employed in dissuading them from it.

en

Recherche sur la nature et les causes de la richesse des nations (1776), Livre I, Livre IV

Variante: Mais le revenu annuel de toute société est toujours précisément égal à la valeur échangeable de tout le produit annuel de son industrie, ou plutôt c'est précisément la même chose que cette valeur échangeable. Par conséquent, puisque chaque individu tâche, le plus qu'il peut, 1° d'employer son capital à faire valoir l'industrie nationale, et - 2° de diriger cette industrie de manière à lui faire produire la plus grande valeur possible, chaque individu travaille nécessairement à rendre aussi grand que possible le revenu annuel de la société. A la vérité, son intention, en général, n'est pas en cela de servir l'intérêt public, et il ne sait même pas jusqu'à quel point il peut être utile à la société. En préférant le succès de l'industrie nationale à celui de l'industrie étrangère, il ne pense qu'à se donner personnellement une plus grande sûreté; et en dirigeant cette industrie de manière à ce que son produit ait le plus de valeur possible, il ne pense qu'à son propre gain; en cela, comme dans beaucoup d'autres cas, il est conduit par une main invisible à remplir une fin qui n'entre nullement dans ses intentions; et ce n'est pas toujours ce qu'il y a de plus mal pour la société, que cette fin n'entre pour rien dans ses intentions. Tout en ne cherchant que son intérêt personnel, il travaille souvent d'une manière bien plus efficace pour l'intérêt de la société, que s'il avait réellement pour but d'y travailler. Je n'ai jamais vu que ceux qui aspiraient, dans leurs entreprises de commerce, à travailler pour le bien général, aient fait beaucoup de bonnes choses. Il est vrai que cette belle passion n'est pas très commune parmi les marchands, et qu'il ne faudrait pas de longs discours pour les en guérir.

en

Recherche sur la nature et les causes de la richesse des nations (1776), Livre I, Livre II

Lectures on Justice, Police, Revenue and Arms (1763)

en

Recherche sur la nature et les causes de la richesse des nations (1776), Livre I

To take an example, therefore, from a very trifling manufacture; but one in which the division of labour has been very often taken notice of, the trade of the pin-maker; a workman not educated to this business (which the division of labour has rendered a distinct trade), nor acquainted with the use of the machinery employed in it (to the invention of which the same division of labour has probably given occasion), could scarce, perhaps, with his utmost industry, make one pin in a day, and certainly could not make twenty. But in the way in which this business is now carried on, not only the whole work is a peculiar trade, but it is divided into a number of branches, of which the greater part are likewise peculiar trades. One man draws out the wire, another straights it, a third cuts it, a fourth points it, a fifth grinds it at the top for receiving, the head; to make the head requires two or three distinct operations; to put it on is a peculiar business, to whiten the pins is another; it is even a trade by itself to put them into the paper; and the important business of making a pin is, in this manner, divided into about eighteen distinct operations, which, in some manufactories, are all performed by distinct hands, though in others the same man will sometimes perform two or three of them. I have seen a small manufactory of this kind where ten men only were employed, and where some of them consequently performed two or three distinct operations. But though they were very poor, and therefore but indifferently accommodated with the necessary machinery, they could, when they exerted themselves, make among them about twelve pounds of pins in a day. There are in a pound upwards of four thousand pins of a middling size. Those ten persons, therefore, could make among them upwards of forty-eight thousand pins in a day. Each person, therefore, making a tenth part of forty-eight thousand pins, might be considered as making four thousand eight hundred pins in a day. But if they had all wrought separately and independently, and without any of them having been educated to this peculiar business, they certainly could not each of them have made twenty, perhaps not one pin in a day; that is, certainly, not the two hundred and fortieth, perhaps not the four thousand eight hundredth part of what they are at present capable of performing, in consequence of a proper division and combination of their different operations.

en

Recherche sur la nature et les causes de la richesse des nations (1776), Livre I

en

Recherche sur la nature et les causes de la richesse des nations (1776), Livre I, Livre III

The Wealth of Nations

The Wealth of Nations

The Wealth of Nations

The Wealth of Nations

The Wealth of Nations

Adam Smith: Citations en anglais

“Fear is in almost all cases a wretched instrument of government”

Source: The Wealth of Nations (1776), Book V, Chapter I, Part III, p. 862.

Contexte: Fear is in almost all cases a wretched instrument of government, and ought in particular never to be employed against any order of men who have the smallest pretensions to independency.

Source: The Wealth of Nations (1776), Book IV, Chapter I, p. 481.

Contexte: The commodities of Europe were almost all new to America, and many of those of America were new to Europe. A new set of exchanges, therefore, began.. and which should naturally have proved as advantageous to the new, as it certainly did to the old continent. The savage injustice of the Europeans rendered an event, which ought to have been beneficial to all, ruinous and destructive to several of those unfortunate countries.

Source: The Wealth of Nations (1776), Book III, Chapter IV, p. 448.

Source: (1776), Book V, Chapter I, Part II, 775.

“Never complain of that of which it is at all times in your power to rid yourself.”

Source: The Theory Of Moral Sentiments

Source: (1776), Book I, Chapter VIII, p. 94.

“Mercy to the guilty is cruelty to the innocent.”

Section II, Chap. III.

The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759), Part II

Source: The Wealth of Nations (1776), Book V, Chapter II, Part II, Article I, p. 911.

Contexte: The necessaries of life occasion the great expense of the poor. They find it difficult to get food, and the greater part of their little revenue is spent in getting it. The luxuries and vanities of life occasion the principal expense of the rich, and a magnificent house embellishes and sets off to the best advantage all the other luxuries and vanities which they possess. A tax upon house-rents, therefore, would in general fall heaviest upon the rich; and in this sort of inequality there would not, perhaps, be anything very unreasonable. It is not very unreasonable that the rich should contribute to the public expense, not only in proportion to their revenue, but something more than in that proportion.

Source: The Wealth of Nations (1776), Book I, Chapter X, Part II, p. 152.

Contexte: People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices. It is impossible indeed to prevent such meetings, by any law which either could be executed, or would be consistent with liberty or justice. But though the law cannot hinder people of the same trade from sometimes assembling together, it ought to do nothing to facilitate such assemblies; much less to render them necessary.

“Wherever there is great property, there is great inequality.”

Source: (1776), Book V, Chapter I, Part II, p. 770.

Source: The Wealth of Nations

Section I, Chap. I.

The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759), Part I

Source: (1776), Book I, Chapter II, p. 14.

Source: The Wealth of Nations

“It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker”

Source: The Wealth of Nations (1776), Book I, Chapter II, p. 19.

Source: The Wealth of Nations, Books 1-3

Contexte: But man has almost constant occasion for the help of his brethren, and it is in vain for him to expect it from their benevolence only. He will be more likely to prevail if he can interest their self-love in his favour, and shew them that it is for their own advantage to do for him what he requires of them. Whoever offers to another a bargain of any kind, proposes to do this. Give me that which I want, and you shall have this which you want, is the meaning of every such offer; and it is in this manner that we obtain from one another the far greater part of those good offices which we stand in need of. It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest. We address ourselves, not to their humanity, but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our own necessities, but of their advantages. Nobody but a beggar chooses to depend chiefly upon the benevolence of his fellow-citizens.

Source: (1776), Book IV, Chapter I, p. 469.

Source: (1776), Book IV, Chapter II

Source: (1776), Book IV, Chapter VII, Part First, p. 610.

Source: (1776), Book I, Chapter X, Part II, p. 155.

Section I, Chap. III.

The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759), Part I

Source: (1776), Book IV, Chapter II

“It seldom happens, however, that a great proprietor is a great improver.”

Source: (1776), Book III, Chapter IV, p. 420.

Source: (1776), Book V, Chapter II, Part II, Article IV, p. 954-955.

Source: (1776), Book V, Chapter I, Part III, Article I, p. 810.

Source: (1776), Book V, Chapter II, Part II, Appendix to Articles I and II.

“The world neither ever saw, nor ever will see, a perfectly fair lottery.”

Chapter X, Part I http://books.google.com/books?id=QItKAAAAYAAJ&q=%22The+world+neither+ever+saw+nor+ever+will+see+a+perfectly+fair+lottery%22&pg=PA76#v=onepage.

(1776), Book I