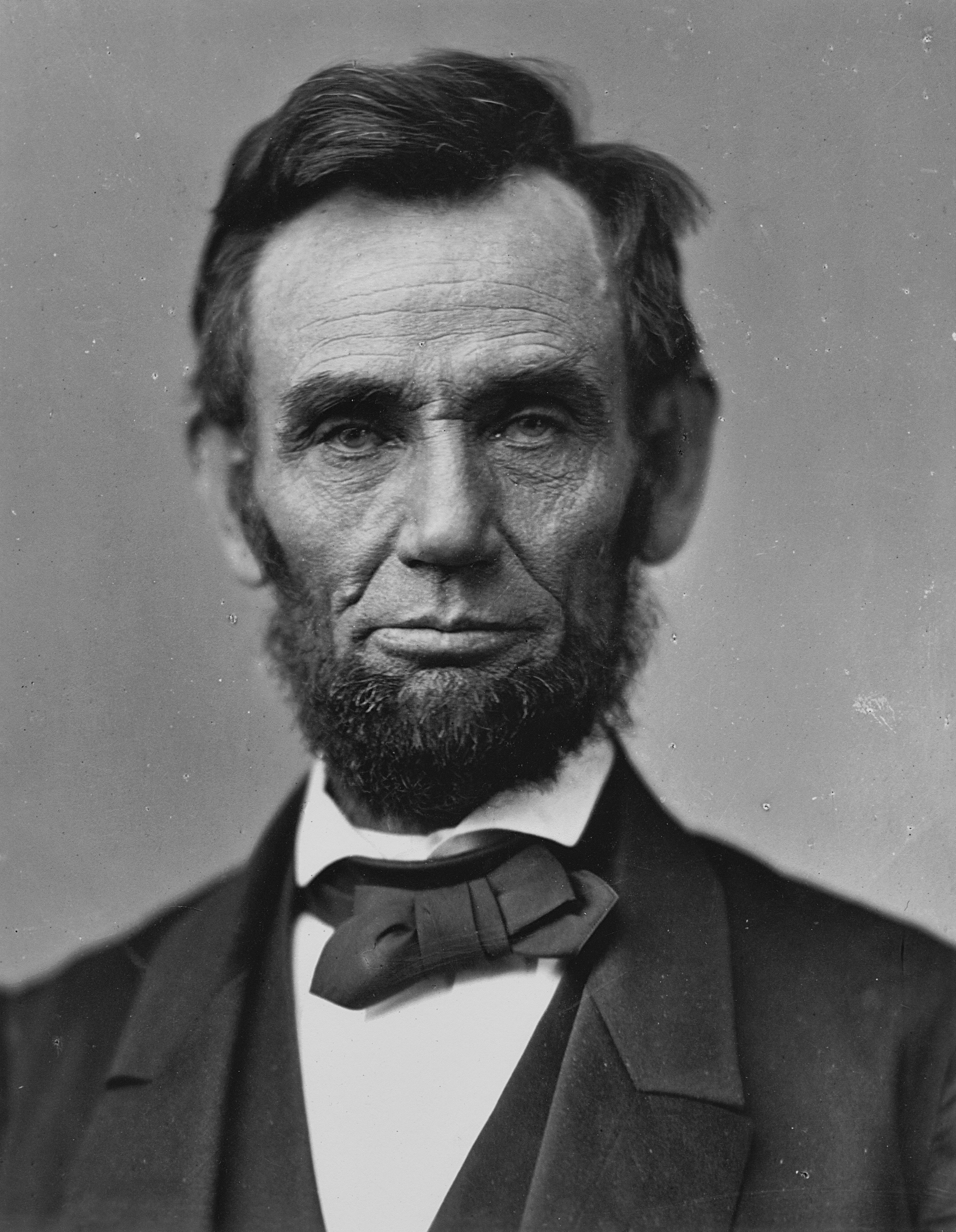

Abraham Lincoln citations célèbres

I will say, then, that I am not nor have ever been in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the black and white races, that I am not, nor ever have been, in favor of making voters or jurors of negroes, nor of qualifying them to hold office, nor to intermarry with White people; and I will say in addition to this that there is a physical difference between the White and black races which will ever forbid the two races living together on terms of social and political equality. And inasmuch as they cannot so live, while they do remain together, there must be the position of

Speeches and Writings, 1832-1858

IT IS RATHER FOR US TO BE HERE DEDICATED TO THE GREAT TASK REMAINING BEFORE US~THAT FROM THESE HONORED DEAD WE TAKE INCREASED DEVOTION TO THAT CAUSE FOR WHICH THEY GAVE THE LAST FULL MEASURE OF DEVOTION~THAT WE HERE HIGHLY RESOLVE THAT THESE DEAD SHALL NOT HAVE DIED IN VAIN~THAT THIS NATION UNDER GOD SHALL HAVE A NEW BIRTH OF FREEDOM~AND THAT GOVERNMENT OF THE PEOPLE BY THE PEOPLE FOR THE PEOPLE SHALL NOT PERISH FROM THE EARTH •

en

Adresse de Gettysburg : gouvernement du peuple, par le peuple, pour le peuple, 1863

Abraham Lincoln: Citations en anglais

“Military glory, — that attractive rainbow that rises in showers of blood.”

Speech in the United States House of Representatives opposing the Mexican war ( 12 January 1848 http://books.google.com/books?id=wiuRyJK6OocC&pg=PA106&dq=rainbow)

1840s

As quoted in Life on the Circuit with Lincoln (1892) by Henry Clay Witney

Posthumous attributions

To the 1864 general conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church, as quoted in Abraham Lincoln : A History Vol. 6 (1890) by John George Nicolay and John Hay, Ch. 15, p. 324

1860s

1860s, Last public address (1865)

“Don't believe everything you read on the Internet.”

This quote is frequently purposefully misattributed to Lincoln or others long dead before the age of the internet in order to emphasize its point using humour; not all such attributions, or other claims, found on the Internet are as obviously flawed. " "Cite and sound: the pleasures and pitfalls of quoting people", by Tom Calverley, The Guardian (14 October 2014) http://www.theguardian.com/media/mind-your-language/2014/oct/14/mind-your-language-quotations

Variations:

Don't believe everything you read online.

Don't trust everything you see on the Internet.

Everything you read on the Internet is true.

The trouble with quotes on the internet is that you never know whether or not they're genuine.

Misattributed

1860s, Second State of the Union address (1862)

p, 125

1850s, Autobiographical Sketch Written for Jesse W. Fell (1859)

Reply to delegation from the National Union League approving and endorsing "the nominations made by the Union National Convention at Baltimore." New York Times, Herald, and Tribune (10 June 1864) Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln. Volume 7 http://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=lincoln;rgn=div1;view=text;idno=lincoln7;node=lincoln7%3A852

To a delegation of the National Union League who congratulated him on his nomination as the Republican candidate for President, June 9, 1864. As given by J. F. Rhodes—Hist. of the U. S. from the Compromise of 1850, Volume IV, p. 370. Same in Nicolay and Hay Lincoln's Complete Works, Volume II, p. 532. Different version in Appleton's Cyclopedia. Raymond—Life and Public Services of Abraham Lincoln, Chapter XVIII, p. 500. (Ed. 1865) says Lincoln quotes an old Dutch farmer, "It was best not to swap horses when crossing a stream".

Variante: I do not allow myself to suppose that either the convention or the League, have concluded to decide that I am either the greatest or the best man in America, but rather they have concluded it is not best to swap horses while crossing the river, and have further concluded that I am not so poor a horse that they might not make a botch of it in trying to swap. note

Source: http://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=lincoln;rgn=div1;view=text;idno=lincoln7;node=lincoln7%3A852 Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln. Volume 7

Letter to Ulysses S. Grant http://www.abrahamlincolnonline.org/lincoln/speeches/grant.htm (13 July 1863), Washington, D.C.

1860s

1860s, Second Inaugural Address (1865)

1830s, The Lyceum Address (1838)

1860s, Allow the humblest man an equal chance (1860)

Letter to Allen N. Ford (11 August 1846), reported in Roy Prentice Basler, ed., Abraham Lincoln: His Speeches and Writings (1990 [1946])

1840s

1860s, First State of the Union address (1861)

Address Delivered in Candidacy for the State Legislature (9 March 1832)

1830s

1860s, Second State of the Union address (1862)

“I have always hated slavery, I think as much as any Abolitionist.”

Speech https://cwcrossroads.wordpress.com/2011/01/18/race-and-slavery-north-and-south-some-logical-fallacies/#comment-47560 (10 July 1858)

1850s

Speech https://diplomatdc.wordpress.com/2010/06/05/the-libertarian-attack-on-abraham-lincoln-by-gregory-hilton/ (1859)

1850s

1850s, Address before the Wisconsin State Agricultural Society (1859)

First debate with Stephen Douglas Ottawa, Illinois (21 August 1858)

1850s, Lincoln–Douglas debates (1858)

But since the Lecompton bill no Democrat, within my experience, has ever pretended that he could see the end. That cry has been dropped. They themselves do not pretend, now, that the agitation of this subject has come to an end yet.

1860s, Allow the humblest man an equal chance (1860)

1850s, Speech at Chicago (1858)

Letter to Orville Hickman Browning (22 September 1861)

1860s

1860s, Fourth of July Address to Congress (1861)

1850s, The House Divided speech (1858)

Source: 1850s, Letter to Henry L. Pierce (1859), p. 377

1860s, First State of the Union address (1861)