“I did not kill my father, but I sometimes felt I had helped him on his way.”

Page 9. (Opening line of the book)

The Cement Garden (1978)

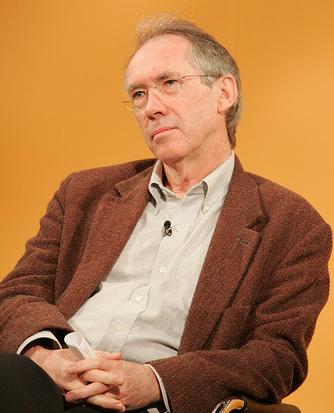

Ian Russell McEwan is an English novelist and screenwriter. In 2008, The Times featured him on their list of "The 50 greatest British writers since 1945", and also in 2008 The Daily Telegraph ranked him number 19 in their list of the "100 most powerful people in British culture".

McEwan began his career writing sparse, Gothic short stories. The Cement Garden and The Comfort of Strangers were his first two novels, and earned him the nickname "Ian Macabre". These were followed by three novels of some success in the 1980s and early 1990s. His work Enduring Love was adapted into a film. He won the Man Booker Prize with Amsterdam . His following novel Atonement garnered acclaim, and was adapted into an Oscar-winning film starring Keira Knightley and James McAvoy. This was followed by Saturday , On Chesil Beach , Solar , Sweet Tooth , The Children Act , and Nutshell . In 2011, he was awarded the Jerusalem Prize.

“I did not kill my father, but I sometimes felt I had helped him on his way.”

Page 9. (Opening line of the book)

The Cement Garden (1978)

Page 34.

Saturday (2005)

From "Faith and Doubt At Ground Zero," Frontline, February, 2002

Source: http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/faith/interviews/mcewan.html

Page 103

The Child in Time (1987)

Page 139. (From the seventh and final short story, 'Psychopolis')

In Between the Sheets (1978)

Page 42.

Sweet Tooth (2012)

Page 164-165.

Black Dogs (1992)