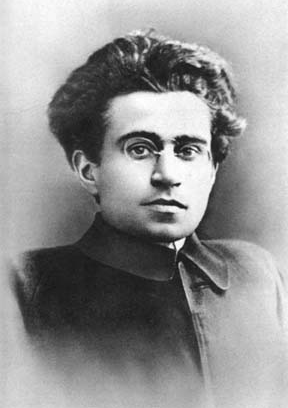

Loose translation, commonly attributed to Gramsci by Slavoj Žižek, presumably formulation by Žižek (see below).

Presumably a translation from a loose French translation by Gustave Massiah; strict English with cognate terms and glosses:

Le vieux monde se meurt, le nouveau monde tarde à apparaître et dans ce clair-obscur surgissent les monstres

The old world is dying, the new world tardy (slow) to appear and in this chiaroscuro (light-dark) surge (emerge) monsters.

“ Mongo Beti, une conscience noire, africaine, universelle http://www.liberationafrique.org/imprimersans.php3?id_article=16&nom_site=Lib%C3%A9ration”, Gustave Massiah, CEDETIM, août 2002 ( archive https://web.archive.org/web/20160304061734/http://www.liberationafrique.org/imprimersans.php3?id_article=16&nom_site=Lib%C3%A9ration, 2016-03-04)

“Mongo Beti, a Black, African, Universal Conscience”, Gustave Massiah, CEDETIM, August 2002

Collected in: Remember Mongo Beti, Ambroise Kom, 2003, p. 149 https://books.google.com/books?id=6YgdAQAAIAAJ&q=%22Le+vieux+monde+se+meurt,+le+nouveau+monde+tarde+%C3%A0+appara%C3%AEtre+et+dans+ce+clair-obscur+surgissent+les+monstres%22.

Original, with literal English translation (see above):

La crisi consiste appunto nel fatto che il vecchio muore e il nuovo non può nascere: in questo interregno si verificano i fenomeni morbosi piú svariati.

The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.

Similar sentiments are widespread in revolutionary rhetoric; see: No, Žižek did not attribute a Goebbels quote to Gramsci http://thecharnelhouse.org/2015/07/03/no-zizek-did-not-attribute-a-goebbels-quote-to-gramsci/, Ross Wolfe, 2015-07-03

Misattributed

Źródło: Selections from the Prison Notebooks