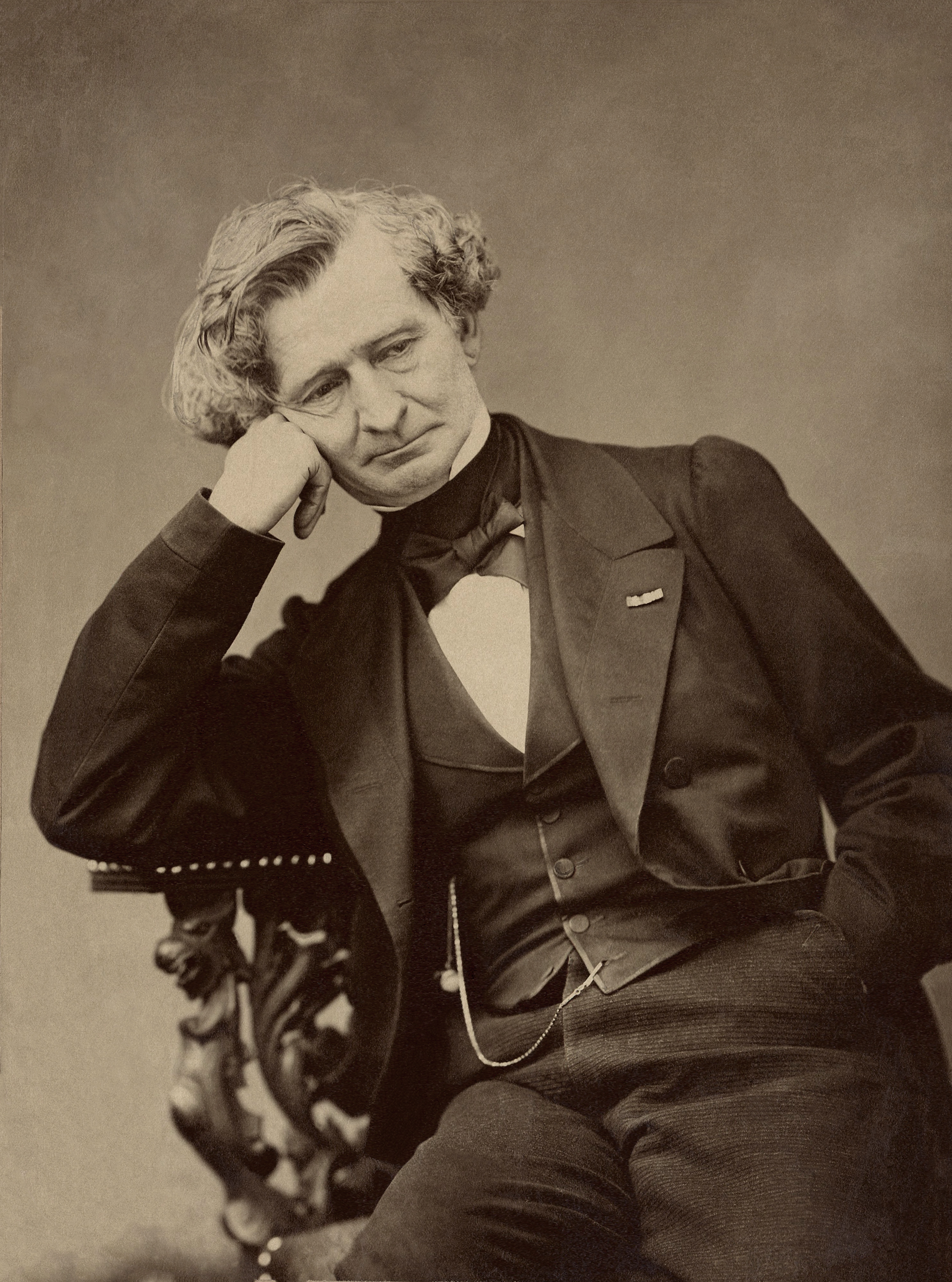

Louis Hector Berlioz francia romantikus zeneszerző, karmester, író, zenekritikus.

Orvosi tanulmányait félbehagyva tért át a zeneszerzésre. Miután a párizsi konzervatóriumban tanulva, több ízben pályázott sikertelenül a Római Díjra, 1828-ban megrendezte első nyilvános szerzői estjét. 1830-ban, a Fantasztikus szimfónia befejezése után, Szardanapál utolsó éjszakája című kantátájával végre elnyerte az áhított elismerést, és Rómába utazott, ahol azonban nem találta helyét, és félbeszakítva az ösztöndíj feltételéül szabott ott-tartózkodást, visszatért a francia fővárosba. 1833-tól mint zeneíró és -kritikus működött. Egész élete során úgy érezte, hogy a párizsi közönség nem értékeli kellőképpen művészetét. Nem sikerült tanári állást szereznie a konzervatóriumban, és az Opérában sem alkalmazták karmesterként. Zűrös magánéletéből a belgiumi és a németországi hangversenykörutak jelentettek számára menekülést. Később Közép-Európába is eljutott, így többek között Pestre is.

Műveinek java programzene, irodalmi eredetű témák feldolgozása, fantáziadús zenei színekkel. Jellemző vonásuk az egységet biztosító visszatérő téma. Elismert karmester volt. Művei nyitányok, szimfóniák, kórusművek, operák, dalok. Meghangszerelte a Rákóczi-indulót, és belefoglalta a Faust elkárhozása című szimfonikus művébe. Leghíresebb műve a Fantasztikus szimfónia, amelyben először alkalmazta a tételeken végigvonuló vezérmotívumot, amely mindig új hangulatot, érzelmet hoz. Az elsők között volt, akik a művész legbensőbb érzéseit, szenvedéseit zenei vallomássá, programzenei alkotássá formálták. Hangszereléstana máig alapvető kézikönyv, ő a máig érvényes, modern szimfonikus hangzás megteremtője: nagy létszámú zenekarra, kórusra írta műveit; és az alapvető ütőhangszerek nála nyerték el állandó helyüket a zenekarban. Élete utolsó szakaszában fordult az operaszínpad felé, ekkor írta meg nagy sikerű nagyoperáját A trójaiak címmel. Az utókorra gyakorolt hatását tekintve az egyik legfontosabb romantikus alkotónak tekinthető, mely hatás a Liszt Ferencen, Wagneren, Verdin és Mahleren át egészen Richard Straussig húzódó szimfonikus ív számos jelentős zeneszerzőjének műveiben megfigyelhető.

Wikipedia

✵

11. december 1803 – 8. március 1869

•

Más nevek

Louis Hector Berlioz