As quoted in American Magazine (September 1908)

Kontextus: A sensitive man is not happy as President. It is fight, fight, fight all the time. I looked forward to the close of my term as a happy release from care. But I am not sure I wasn't more unhappy out of office than in. A term in the presidency accustoms a man to great duties. He gets used to handling tremendous enterprises, to organizing forces that may affect at once and directly the welfare of the world. After the long exercise of power, the ordinary affairs of life seem petty and commonplace. An ex-President practicing law or going into business is like a locomotive hauling a delivery wagon. He has lost his sense of proportion. The concerns of other people and even his own affairs seem too small to be worth bothering about.

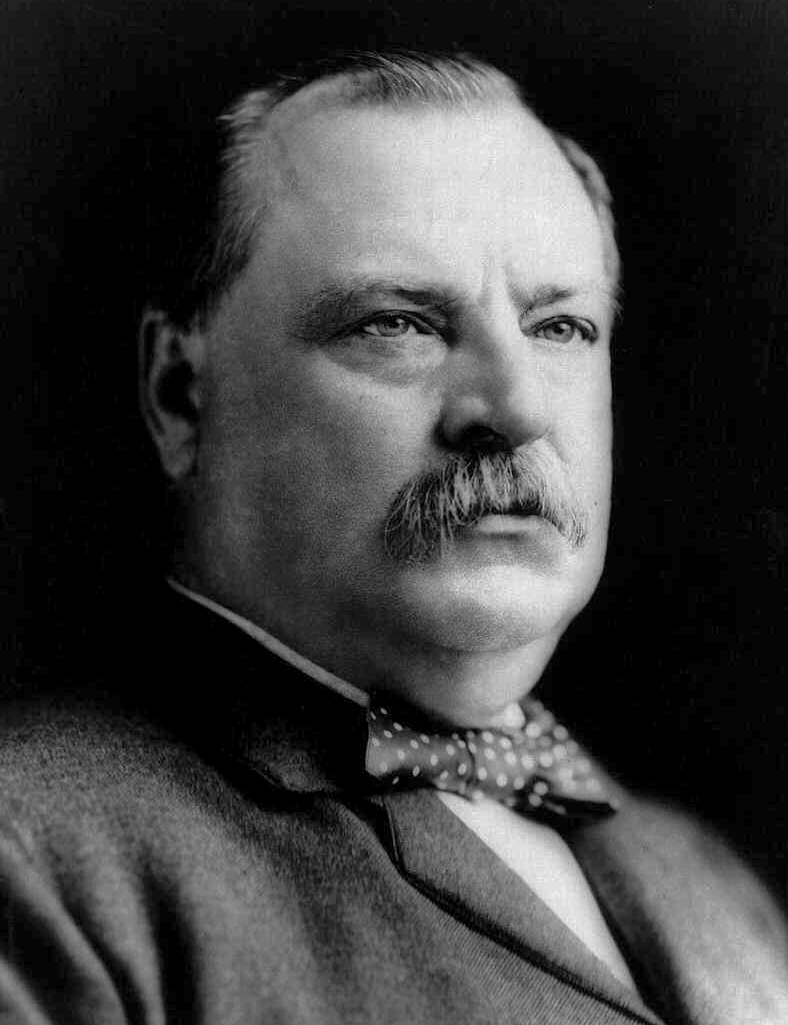

Grover Cleveland: Idézetek angolul

First Inaugural Address (4 March 1885)

Kontextus: The laws and the entire scheme of our civil rule, from the town meeting to the State capitals and the national capital, is yours. Your every voter, as surely as your Chief Magistrate, under the same high sanction, though in a different sphere, exercises a public trust. Nor is this all. Every citizen owes to the country a vigilant watch and close scrutiny of its public servants and a fair and reasonable estimate of their fidelity and usefulness. Thus is the people's will impressed upon the whole framework of our civil polity — municipal, State, and Federal; and this is the price of our liberty and the inspiration of our faith in the Republic.

Message to Congress withdrawing a treaty for the annexation of Hawaii from consideration. (18 December 1893); A Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the Presidents 1789-1897 (1896 - 1899) edited by James D. Richardson, Vol. IX, pp. 460-472.

Kontextus: It has been the boast of our government that it seeks to do justice in all things without regard to the strength or weakness of those with whom it deals. I mistake the American people if they favor the odious doctrine that there is no such thing as international morality; that there is one law for a strong nation and another for a weak one, and that even by indirection a strong power may with impunity despoil a weak one of its territory.

By an act of war, committed with the participation of a diplomatic representative of the United States and without authority of Congress, the government of a feeble but friendly and confiding people has been overthrown. A substantial wrong has thus been done which a due regard for our national character as well as the rights of the injured people requires we should endeavor to repair. The Provisional Government has not assumed a republican or other constitutional form, but has remained a mere executive council or oligarchy, set up without the assent of the people. It has not sought to find a permanent basis of popular support and has given no evidence of an intention to do so. Indeed, the representatives of that government assert that the people of Hawaii are unfit for popular government and frankly avow that they can be best ruled by arbitrary or despotic power.

The law of nations is founded upon reason and justice, and the rules of conduct governing individual relations between citizens or subjects of a civilized state are equally applicable as between enlightened nations. The considerations that international law is without a court for its enforcement and that obedience to its commands practically depends upon good faith instead of upon the mandate of a superior tribunal only give additional sanction to the law itself and brand any deliberate infraction of it not merely as a wrong but as a disgrace. A man of true honor protects the unwritten word which binds his conscience more scrupulously, if possible, than he does the bond a breach of which subjects him to legal liabilities, and the United States, in aiming to maintain itself as one of the most enlightened nations, would do its citizens gross injustice if it applied to its international relations any other than a high standard of honor and morality.

On that ground the United States cannot properly be put in the position of countenancing a wrong after its commission any more than in that of consenting to it in advance. On that ground it cannot allow itself to refuse to redress an injury inflicted through an abuse of power by officers clothed with its authority and wearing its uniform; and on the same ground, if a feeble but friendly state is in danger of being robbed of its independence and its sovereignty by a misuse of the name and power of the United States, the United States cannot fail to vindicate its honor and its sense of justice by an earnest effort to make all possible reparation.

Letter to the Democratic Convention (17 August 1884).

Kontextus: A truly American sentiment recognizes the dignity of labor and the fact that honor lies in honest toil. Contented labor is an element of national prosperity. Ability to work constitutes the capital and the wage of labor the income of a vast number of our population, and this interest should be jealously protected. Our workingmen are not asking unreasonable indulgence, but as intelligent and manly citizens they seek the same consideration which those demand who have other interests at stake. They should receive their full share of the care and attention of those who make and execute the laws, to the end that the wants and needs of the employers and the employed shall alike be subserved and the prosperity of the country, the common heritage of both, be advanced.

Letter to his brother Rev. William N. Cleveland (7 November 1882); published in The Writings and Speeches of Grover Cleveland (1892), p. 534.

Kontextus: I feel as if it were time for me to write to someone who will believe what I write.

I have been for some time in the atmosphere of certain success, so that I have been sure that I should assume the duties of the high office for which I have been named. I have tried hard, in the light of this fact, to appreciate properly the responsibilities that will rest upon me, and they are much, too much underestimated. But the thought that has troubled me is, can I well perform my duties, and in such a manner as to do some good to the people of the State? I know there is room for it, and I know that I am honest and sincere in my desire to do well; but the question is whether I know enough to accomplish what I desire.

The social life which seems to await me has also been a subject of much anxious thought. I have a notion that I can regulate that very much as I desire; and, if I can, I shall spend very little time in the purely ornamental part of the office. In point of fact, I will tell you, first of all others, the policy I intend to adopt, and that is, to make the matter a business engagement between the people of the State and myself, in which the obligation on my side is to perform the duties assigned me with an eye single to the interest of my employers. I shall have no idea of re-election, or any higher political preferment in my head, but be very thankful and happy I can serve one term as the people's Governor.

Dedication speech http://www.endex.com/gf/buildings/liberty/nytc/solnytc1943.htm for the Statue of Liberty (28 October 1886).

Kontextus: We are not here today to bow before the representation of a fierce warlike god, filled with wrath and vengeance, but we joyously contemplate instead our own deity keeping watch and ward before the open gates of America and greater than all that have been celebrated in ancient song. Instead of grasping in her hand thunderbolts of terror and of death, she holds aloft the light which illumines the way to man's enfranchisement. We will not forget that Liberty has here made her home, nor shall her chosen altar be neglected. Willing votaries will constantly keep alive its fires and these shall gleam upon the shores of our sister Republic thence, and joined with answering rays a stream of light shall pierce the darkness of ignorance and man's oppression, until Liberty enlightens the world.

“Communism is a hateful thing and a menace to peace and organized government”

Fourth Annual Message (3 December 1888)

Kontextus: Communism is a hateful thing and a menace to peace and organized government; but the communism of combined wealth and capital, the outgrowth of overweening cupidity and selfishness, which insidiously undermines the justice and integrity of free institutions, is not less dangerous than the communism of oppressed poverty and toil, which, exasperated by injustice and discontent, attacks with wild disorder the citadel of rule.

He mocks the people who proposes that the Government shall protect the rich and that they in turn will care for the laboring poor. Any intermediary between the people and their Government or the least delegation of the care and protection the Government owes to the humblest citizen in the land makes the boast of free institutions a glittering delusion and the pretended boon of American citizenship a shameless imposition.

Message to Congress withdrawing a treaty for the annexation of Hawaii from consideration. (18 December 1893); A Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the Presidents 1789-1897 (1896 - 1899) edited by James D. Richardson, Vol. IX, pp. 460-472.

Kontextus: It has been the boast of our government that it seeks to do justice in all things without regard to the strength or weakness of those with whom it deals. I mistake the American people if they favor the odious doctrine that there is no such thing as international morality; that there is one law for a strong nation and another for a weak one, and that even by indirection a strong power may with impunity despoil a weak one of its territory.

By an act of war, committed with the participation of a diplomatic representative of the United States and without authority of Congress, the government of a feeble but friendly and confiding people has been overthrown. A substantial wrong has thus been done which a due regard for our national character as well as the rights of the injured people requires we should endeavor to repair. The Provisional Government has not assumed a republican or other constitutional form, but has remained a mere executive council or oligarchy, set up without the assent of the people. It has not sought to find a permanent basis of popular support and has given no evidence of an intention to do so. Indeed, the representatives of that government assert that the people of Hawaii are unfit for popular government and frankly avow that they can be best ruled by arbitrary or despotic power.

The law of nations is founded upon reason and justice, and the rules of conduct governing individual relations between citizens or subjects of a civilized state are equally applicable as between enlightened nations. The considerations that international law is without a court for its enforcement and that obedience to its commands practically depends upon good faith instead of upon the mandate of a superior tribunal only give additional sanction to the law itself and brand any deliberate infraction of it not merely as a wrong but as a disgrace. A man of true honor protects the unwritten word which binds his conscience more scrupulously, if possible, than he does the bond a breach of which subjects him to legal liabilities, and the United States, in aiming to maintain itself as one of the most enlightened nations, would do its citizens gross injustice if it applied to its international relations any other than a high standard of honor and morality.

On that ground the United States cannot properly be put in the position of countenancing a wrong after its commission any more than in that of consenting to it in advance. On that ground it cannot allow itself to refuse to redress an injury inflicted through an abuse of power by officers clothed with its authority and wearing its uniform; and on the same ground, if a feeble but friendly state is in danger of being robbed of its independence and its sovereignty by a misuse of the name and power of the United States, the United States cannot fail to vindicate its honor and its sense of justice by an earnest effort to make all possible reparation.

“I feel as if it were time for me to write to someone who will believe what I write.”

Letter to his brother Rev. William N. Cleveland (7 November 1882); published in The Writings and Speeches of Grover Cleveland (1892), p. 534.

Kontextus: I feel as if it were time for me to write to someone who will believe what I write.

I have been for some time in the atmosphere of certain success, so that I have been sure that I should assume the duties of the high office for which I have been named. I have tried hard, in the light of this fact, to appreciate properly the responsibilities that will rest upon me, and they are much, too much underestimated. But the thought that has troubled me is, can I well perform my duties, and in such a manner as to do some good to the people of the State? I know there is room for it, and I know that I am honest and sincere in my desire to do well; but the question is whether I know enough to accomplish what I desire.

The social life which seems to await me has also been a subject of much anxious thought. I have a notion that I can regulate that very much as I desire; and, if I can, I shall spend very little time in the purely ornamental part of the office. In point of fact, I will tell you, first of all others, the policy I intend to adopt, and that is, to make the matter a business engagement between the people of the State and myself, in which the obligation on my side is to perform the duties assigned me with an eye single to the interest of my employers. I shall have no idea of re-election, or any higher political preferment in my head, but be very thankful and happy I can serve one term as the people's Governor.

Letter to the Democratic Convention (17 August 1884).

Kontextus: A truly American sentiment recognizes the dignity of labor and the fact that honor lies in honest toil. Contented labor is an element of national prosperity. Ability to work constitutes the capital and the wage of labor the income of a vast number of our population, and this interest should be jealously protected. Our workingmen are not asking unreasonable indulgence, but as intelligent and manly citizens they seek the same consideration which those demand who have other interests at stake. They should receive their full share of the care and attention of those who make and execute the laws, to the end that the wants and needs of the employers and the employed shall alike be subserved and the prosperity of the country, the common heritage of both, be advanced.

“Officeholders are the agents of the people, not their masters.”

Message to the heads of departments in the service of the US Government (14 July 1886).

Kontextus: Officeholders are the agents of the people, not their masters. Not only is their time and labor due to the Government, but they should scrupulously avoid in their political action, as well as in the discharge of their official duty, offending by a display of obtrusive partisanship their neighbors who have relations with them as public officials.

First Inaugural Address (4 March 1885).

Kontextus: Amid the din of party strife the people's choice was made, but its attendant circumstances have demonstrated anew the strength and safety of a government by the people. In each succeeding year it more clearly appears that our democratic principle needs no apology, and that in its fearless and faithful application is to be found the surest guaranty of good government.

But the best results in the operation of a government wherein every citizen has a share largely depend upon a proper limitation of purely partisan zeal and effort and a correct appreciation of the time when the heat of the partisan should be merged in the patriotism of the citizen.

“It is a condition which confronts us — not a theory.”

Third Annual Message to Congress (6 December 1887), discussing tariffs. Compare "Free trade is not a principle, it is an expedient", Benjamin Disraeli, On Import Duties, April 25, 1843.

Kontextus: Both of the great political parties now represented in the Government have by repeated and authoritative declarations condemned the condition of our laws which permit the collection from the people of unnecessary revenue, and have in the most solemn manner promised its correction; and neither as citizens nor partisans are our countrymen in a mood to condone the deliberate violation of these pledges.

Our progress toward a wise conclusion will not be improved by dwelling upon the theories of protection and free trade. This savors too much of bandying epithets. It is a condition which confronts us — not a theory. Relief from this condition may involve a slight reduction of the advantages which we award our home productions, but the entire withdrawal of such advantages should not be contemplated. The question of free trade is absolutely irrelevant, and the persistent claim made in certain quarters that all the efforts to relieve the people from unjust and unnecessary taxation are schemes of so-called free traders is mischievous and far removed from any consideration for the public good.

Letter to his brother Rev. William N. Cleveland (7 November 1882); published in The Writings and Speeches of Grover Cleveland (1892), p. 534.

Kontextus: I feel as if it were time for me to write to someone who will believe what I write.

I have been for some time in the atmosphere of certain success, so that I have been sure that I should assume the duties of the high office for which I have been named. I have tried hard, in the light of this fact, to appreciate properly the responsibilities that will rest upon me, and they are much, too much underestimated. But the thought that has troubled me is, can I well perform my duties, and in such a manner as to do some good to the people of the State? I know there is room for it, and I know that I am honest and sincere in my desire to do well; but the question is whether I know enough to accomplish what I desire.

The social life which seems to await me has also been a subject of much anxious thought. I have a notion that I can regulate that very much as I desire; and, if I can, I shall spend very little time in the purely ornamental part of the office. In point of fact, I will tell you, first of all others, the policy I intend to adopt, and that is, to make the matter a business engagement between the people of the State and myself, in which the obligation on my side is to perform the duties assigned me with an eye single to the interest of my employers. I shall have no idea of re-election, or any higher political preferment in my head, but be very thankful and happy I can serve one term as the people's Governor.

Fourth Annual Message (3 December 1888)

Kontextus: Communism is a hateful thing and a menace to peace and organized government; but the communism of combined wealth and capital, the outgrowth of overweening cupidity and selfishness, which insidiously undermines the justice and integrity of free institutions, is not less dangerous than the communism of oppressed poverty and toil, which, exasperated by injustice and discontent, attacks with wild disorder the citadel of rule.

He mocks the people who proposes that the Government shall protect the rich and that they in turn will care for the laboring poor. Any intermediary between the people and their Government or the least delegation of the care and protection the Government owes to the humblest citizen in the land makes the boast of free institutions a glittering delusion and the pretended boon of American citizenship a shameless imposition.

“Party honesty is party expediency.”

Interview in New York Commercial Advertiser (19 September 1889).

“What is the use of being elected or re-elected unless you stand for something?”

As quoted in An Honest President (2000) by H. Paul Jeffers, p. 200.

Second Annual Message (December 1886).

Letter accepting the nomination for governor of New York (October 1882).

"Veto of the Texas Seed Bill" (16 February 1887)

“I have tried so hard to do the right.”

Last words, as quoted in Just a Country Lawyer: A Biography of Senator Sam Ervin (1974) by Paul R. Clancy.

Speech in New York (12 February 1904), as quoted in speech by Edward de Veaux Morrell https://cdn.loc.gov/service/rbc/lcrbmrp/t2609/t2609.pdf (April 1904)

“WHATEVER YOU DO, TELL THE TRUTH.”

Telegram to his friend Charles W. Goodyear (23 July 1884), in response to a query as to what the Democratic Party should say about reports that he fathered a child out of wedlock. As quoted in An Honest President (2000), by H. Paul Jeffers, p. 108.

Letter to Representative Thomas C. Catchings (27 August 1894), reported in Letters of Grover Cleveland, 1850–1908, ed. Allan Nevins (1933), p. 365

Second Inaugural Address (4 March 1893).

Letter accepting the nomination for governor of New York (October 1882); later quoted in his letter to the Democratic National Convention (18 August 1884).

“I have considered the pension list of the republic a roll of honor.”

Veto of Dependent Pension Bill, July 5, 1888

Message to the US Senate on laws constraining the discretionary powers of the President to remove or suspend officials. (1 March 1886).

Quoted in The American Mercury (1961), in a letter from Cleveland to his law partner, Wilson S. Bissell, February 15th, 1894. https://books.google.com/books?id=BIsqAAAAMAAJ&q=%22The+present+danger%22+cleveland+bissell&dq=%22The+present+danger%22+cleveland+bissell&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwj68-CIhenSAhXpCMAKHdsXCKQQ6AEIHjAB.

At the celebration of the sesquicentennial of Princeton College (October 22, 1896).