Licklider (1950) quotes in: Claude E. Shannon " The redundancy of English http://www.uni-due.de/~bj0063/doc/shannon_redundancy.pdf". In: Claus Pias, Heinz von Foerster eds. (2003) Cybernetics: Transactions. p. 270.

Contexte: It is probably dangerous to use this theory of information in fields for which it was not designed, but I think the danger will not keep people from using it. In psychology, at least in the psychology of communication, it seems to fit with a fair approximation. When it occurs that the learnability of material is roughly proportional to the information content calculated | by the theory, I think it looks interesting. There may have to be modifications, of course. For example, I think that the human receiver of information gets more out of a message that is encoded into a broad vocabulary (an extensive set of symbols) and presented at a slow pace, than from a message, equal in information content, that is encoded into a restricted set of symbols and presented at a faster pace. Nevertheless, the elementary parts of the theory appear to be very useful. I say it may be dangerous to use them, but I don’t think the danger will scare us off.

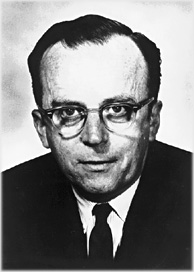

Joseph Carl Robnett Licklider: Citations en anglais

Licklider in: " An Interview with J. C. R. LICKLIDER http://conservancy.umn.edu/bitstream/107436/1/oh150jcl.pdf" conducted by William Aspray and Arthur Norberg on 28 October 1988, Cambridge, MA.

appear on the display.

Source: Libraries of the future, 1965, p. 100 as cited in: Recent advances in display media (1982). Vol. 3, p. 177.

As cited in: Ching-chih Chen (1980) Quantitative measurement and dynamic library service. p. 52.

Libraries of the future, 1965

Source: Libraries of the future, 1965, p. 6 as cited in: Rodney James Giblett (2008) Sublime communication technologies. p. 175.

Cited in: Jacques Berleur, Markku I. Nurminen, John Impagliazzo (2006) Social Informatics: An Information Society for All? p. 436.

Man-Computer Symbiosis, 1960