Vol. I, Ch. 1 : A Man of His Day, p. 17

New Grub Street : A Novel (1891)

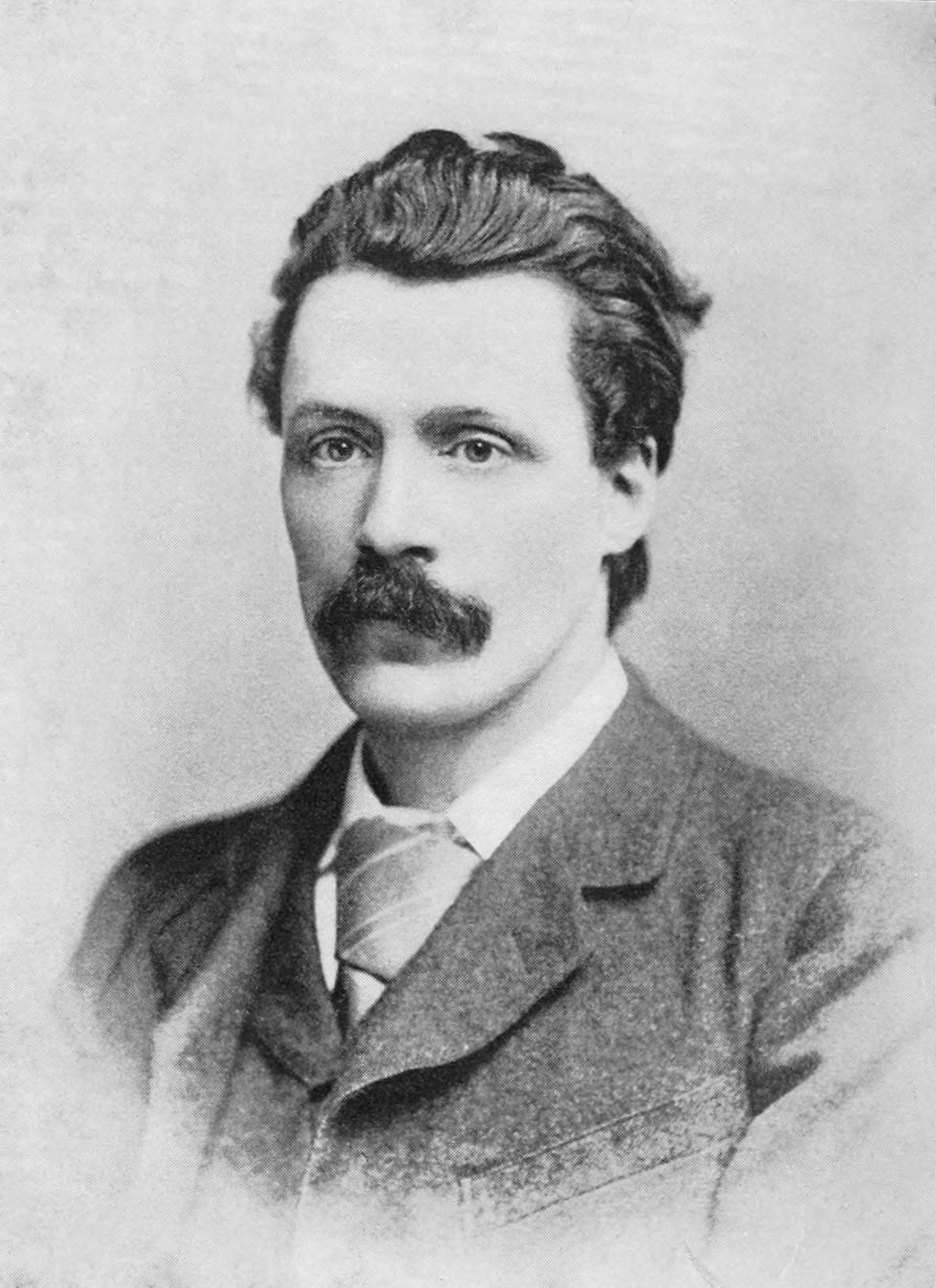

George Gissing: Citations en anglais

The Private Papers of Henry Ryecroft (1903)

Contexte: Time is money — says the vulgarest saw known to any age or people. Turn it round about, and you get a precious truth —money is time. I think of it on these dark, mist-blinded mornings, as I come down to find a glorious fire crackling and leaping in my study. Suppose I were so poor that I could not afford that heartsome blaze, how different the whole day would be! Have I not lost many and many a day of my life for lack of the material comfort which was necessary to put my mind in tune? Money is time. With money I buy for cheerful use the hours which otherwise would not in any sense be mine; nay, which would make me their miserable bondsman. Money is time, and, heaven be thanked, there needs so little of it for this sort of purchase. He who has overmuch is wont to be as badly off in regard to the true use of money, as he who has not enough. What are we doing all our lives but purchasing, or trying to purchase, time? And most of us, having grasped it with one hand, throw it away with the other.

Winter, § 24, p. 287; in Conducting Effective Faculty Meetings (2008) by Sue Ellen Brandenburg, p. 12 this appears paraphrased in the form: "Time is money says the proverb, but turn it around and you get a precious truth. Money is time."

Winter, § 24, p. 287; in Conducting Effective Faculty Meetings (2008) by Sue Ellen Brandenburg, p. 12 this appears paraphrased in the form: "Time is money says the proverb, but turn it around and you get a precious truth. Money is time."

The Private Papers of Henry Ryecroft (1903)

Contexte: Time is money — says the vulgarest saw known to any age or people. Turn it round about, and you get a precious truth —money is time. I think of it on these dark, mist-blinded mornings, as I come down to find a glorious fire crackling and leaping in my study. Suppose I were so poor that I could not afford that heartsome blaze, how different the whole day would be! Have I not lost many and many a day of my life for lack of the material comfort which was necessary to put my mind in tune? Money is time. With money I buy for cheerful use the hours which otherwise would not in any sense be mine; nay, which would make me their miserable bondsman. Money is time, and, heaven be thanked, there needs so little of it for this sort of purchase. He who has overmuch is wont to be as badly off in regard to the true use of money, as he who has not enough. What are we doing all our lives but purchasing, or trying to purchase, time? And most of us, having grasped it with one hand, throw it away with the other.

“Persistent prophecy is a familiar way of assuring the event.”

Summer, § VII, p. 89

The Private Papers of Henry Ryecroft (1903)

Contexte: This writer, who is horribly perspicacious and vigorous, demonstrates the certainty of a great European war, and regards it with the peculiar satisfaction excited by such things in a certain order of mind. His phrases about "dire calamity" and so on mean nothing; the whole tenor of his writing proves that he represents, and consciously, one of the forces which go to bring war about; his part in the business is a fluent irresponsibility, which casts scorn on all who reluct at the "inevitable." Persistent prophecy is a familiar way of assuring the event.

“I maintain that we people of brains are justified in supplying the mob with the food it likes.”

Vol. I, Ch. 1 : A Man of His Day, p. 17

New Grub Street : A Novel (1891)

Contexte: I maintain that we people of brains are justified in supplying the mob with the food it likes. We are not geniuses, and if we sit down in a spirit of long-eared gravity we shall produce only commonplace stuff. Let us use our wits to earn money, and make the best we can of our lives. If only I had the skill, I would produce novels out-trashing the trashiest that ever sold fifty thousand copies. But it needs skill, mind you; and to deny it is a gross error of the literary pedants. To please the vulgar you must, one way or another, incarnate the genius of vulgarity.

“I am learning my business. Literature nowadays is a trade.”

Vol. I, Ch. 1 : A Man of His Day, p. 8

New Grub Street : A Novel (1891)

Contexte: I am learning my business. Literature nowadays is a trade. Putting aside men of genius, who may succeed by mere cosmic force, your successful man of letters is your skilful tradesman. He thinks first and foremost of the markets; when one kind of goods begins to go off slackly, he is ready with something new and appetising. He knows perfectly all the possible sources of income. Whatever he has to sell he'll get payment for it from all sorts of various quarters; none of your unpractical selling for a lump sum to a middleman who will make six distinct profits.

Spring, § I, p. 2

The Private Papers of Henry Ryecroft (1903)

Contexte: Old companion, yet old enemy! How many a time have I taken it up, loathing the necessity, heavy in head and heart, my hand shaking, my eyes sickdazzled! How I dreaded the white page I had to foul with ink! Above all, on days such as this, when the blue eyes of Spring laughed from between rosy clouds, when the sunlight shimmered upon my table and made me long, long all but to madness, for the scent of the flowering earth, for the green of hillside larches, for the singing of the skylark above the downs. There was a time— it seems further away than childhood — when I took up my pen with eagerness; if my hand trembled it was with hope. But a hope that fooled me, for never a page of my writing deserved to live. I can say that now without bitterness. It was youthful error, and only the force of circumstance prolonged it. The world has done me no injustice; thank Heaven I have grown wise enough not to rail at it for this! And why should any man who writes, even if he writes things immortal, nurse anger at the world's neglect? Who asked him to publish? Who promised him a hearing? Who has broken faith with him? If my shoemaker turn me out an excellent pair of boots, and I, in some mood of cantankerous unreason, throw them back upon his hands, the man has just cause of complaint. But your poem, your novel, who bargained with you for it? If it is honest journeywork, yet lacks purchasers, at most you may call yourself a hapless tradesman. If it come from on high, with what decency do you fret and fume because it is not paid for in heavy cash? For the work of man's mind there is one test, and one alone, the judgment of generations yet unborn. If you have written a great book, the world to come will know of it. But you don't care for posthumous glory. You want to enjoy fame in a comfortable armchair. Ah, that is quite another thing. Have the courage of your desire. Admit yourself a merchant, and protest to gods and men that the merchandise you offer is of better quality than much which sells for a high price. You may be right, and indeed it is hard upon you that Fashion does not turn to your stall.

Vol. I, Ch. 1 : A Man of His Day, p. 3

New Grub Street : A Novel (1891)

“To be at other people's orders brings out all the bad in me.”

Will Warburton (1905), ch. 3

As quoted in 'The Book Of Us : A Guide To Scrapbooking About Relationships (2005) Angie Pedersen, p. 46

Source: Our Friend the Charlatan (1901), Ch. XXVIII

As quoted in Quote Junkie Funny Edition (2008) by the Hagopian Institute, p. 47

Source: Our Friend the Charlatan (1901), Ch. II

Winter § I, p. 213

The Private Papers of Henry Ryecroft (1903)

“No, no; women, old or young, should never have to think about money.”

The Odd Women (1893), ch. 1