Section IV, p. 8

Natural Law; or The Science of Justice (1882), Chapter I. The Science of Justice.

Works

No Treason

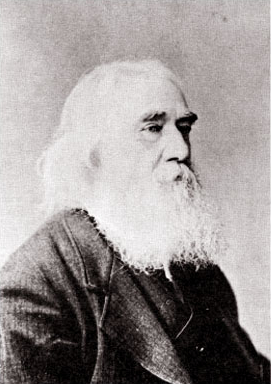

Lysander SpoonerFamous Lysander Spooner Quotes

Source: No Treason (1867–1870), No. I, p. 8

No Treason (1867–1870), No. VI: The Constitution of No Authority

Section II, p. 6

Natural Law; or The Science of Justice (1882), Chapter I. The Science of Justice.

An Essay on the Trial by Jury, Boston, MA: John P. Jewett and Company, Cleveland, Ohio: Jewett, Proctor & Worthington (1852) p. 5

No Treason (1867–1870), No. VI: The Constitution of No Authority

Lysander Spooner Quotes about justice

Section IV, p. 12–13

Natural Law; or The Science of Justice (1882), Chapter II. The Science of Justice (Continued)

Section I, p. 5

Natural Law; or The Science of Justice (1882), Chapter I. The Science of Justice.

Section VIII, p. 15

Natural Law; or The Science of Justice (1882), Chapter II. The Science of Justice (Continued)

Section IV, p. 9–10

Natural Law; or The Science of Justice (1882), Chapter I. The Science of Justice.

Section V, p. 13

Natural Law; or The Science of Justice (1882), Chapter II. The Science of Justice (Continued)

No Treason (1867–1870), No. I

Lysander Spooner Quotes about men

No Treason (1867–1870), No. VI: The Constitution of No Authority

Source: No Treason (1867–1870), No. I, p. 9

Section I, p. 6

Natural Law; or The Science of Justice (1882), Chapter I. The Science of Justice.

Sections I–II, p. 11–12

Natural Law; or The Science of Justice (1882), Chapter II. The Science of Justice (Continued)

No Treason (1867–1870), No. VI: The Constitution of No Authority

Section I, p. 5–6

Natural Law; or The Science of Justice (1882), Chapter I. The Science of Justice.

Lysander Spooner Quotes

Source: No Treason (1867–1870), No. VI: The Constitution of No Authority, p. 24; the first sentence here is widely paraphrased as: A man is no less a slave because he is allowed to choose a new master once in a term of years.

Context: A man is none the less a slave because he is allowed to choose a new master once in a term of years. Neither are a people any the less slaves because permitted periodically to choose new masters. What makes them slaves is the fact that they now are, and are always hereafter to be, in the hands of men whose power over them is, and always is to be, absolute and irresponsible.

The right of absolute and irresponsible dominion is the right of property, and the right of property is the right of absolute, irresponsible dominion. The two are identical; the one necessarily implying the other. Neither can exist without the other. If, therefore, Congress have that absolute and irresponsible lawmaking power, which the Constitution — according to their interpretation of it — gives them, it can only be because they own us as property. If they own us as property, they are our masters, and their will is our law. If they do not own us as property, they are not our masters, and their will, as such, is of no authority over us.

But these men who claim and exercise this absolute and irresponsible dominion over us, dare not be consistent, and claim either to be our masters, or to own us as property. They say they are only our servants, agents, attorneys, and representatives. But this declaration involves an absurdity, a contradiction. No man can be my servant, agent, attorney, or representative, and be, at the same time, uncontrollable by me, and irresponsible to me for his acts. It is of no importance that I appointed him, and put all power in his hands. If I made him uncontrollable by me, and irresponsible to me, he is no longer my servant, agent, attorney, or representative. If I gave him absolute, irresponsible power over my property, I gave him the property. If I gave him absolute, irresponsible power over myself, I made him my master, and gave myself to him as a slave. And it is of no importance whether I called him master or servant, agent or owner. The only question is, what power did I put into his hands? Was it an absolute and irresponsible one? or a limited and responsible one?

Source: No Treason (1867–1870), No. VI: The Constitution of No Authority, p. 12–13

Context: It is true that the theory of our Constitution is, that all taxes are paid voluntarily; that our government is a mutual insurance company, voluntarily entered into by the people with each other; that each man makes a free and purely voluntary contract with all others who are parties to the Constitution, to pay so much money for so much protection, the same as he does with any other insurance company; and that he is just as free not to be protected, and not to pay any tax, as he is to pay a tax, and be protected.But this theory of our government is wholly different from the practical fact. The fact is that the government, like a highwayman, says to a man: Your money, or your life. And many, if not most, taxes are paid under the compulsion of that threat.The government does not, indeed, waylay a man in a lonely place, spring upon him from the road side, and, holding a pistol to his head, proceed to rifle his pockets. But the robbery is none the less a robbery on that account; and it is far more dastardly and shameful.The highwayman takes solely upon himself the responsibility, danger, and crime of his own act. He does not pretend that he has any rightful claim to your money, or that he intends to use it for your own benefit. He does not pretend to be anything but a robber. He has not acquired impudence enough to profess to be merely a "protector," and that he takes men's money against their will, merely to enable him to "protect" those infatuated travellers, who feel perfectly able to protect themselves, or do not appreciate his peculiar system of protection. He is too sensible a man to make such professions as these. Furthermore, having taken your money, he leaves you, as you wish him to do. He does not persist in following you on the road, against your will; assuming to be your rightful "sovereign," on account of the "protection" he affords you. He does not keep "protecting" you, by commanding you to bow down and serve him; by requiring you to do this, and forbidding you to do that; by robbing you of more money as often as he finds it for his interest or pleasure to do so; and by branding you as a rebel, a traitor, and an enemy to your country, and shooting you down without mercy, if you dispute his authority, or resist his demands. He is too much of a gentleman to be guilty of such impostures, and insults, and villainies as these. In short, he does not, in addition to robbing you, attempt to make you either his dupe or his slave.The proceedings of those robbers and murderers, who call themselves "the government," are directly the opposite of these of the single highwayman.In the first place, they do not, like him, make themselves individually known; or, consequently, take upon themselves personally the responsibility of their acts. On the contrary, they secretly (by secret ballot) designate some one of their number to commit the robbery in their behalf, while they keep themselves practically concealed.

Source: No Treason (1867–1870), No. VI: The Constitution of No Authority, p. 12–13

Context: It is true that the theory of our Constitution is, that all taxes are paid voluntarily; that our government is a mutual insurance company, voluntarily entered into by the people with each other; that each man makes a free and purely voluntary contract with all others who are parties to the Constitution, to pay so much money for so much protection, the same as he does with any other insurance company; and that he is just as free not to be protected, and not to pay any tax, as he is to pay a tax, and be protected.But this theory of our government is wholly different from the practical fact. The fact is that the government, like a highwayman, says to a man: Your money, or your life. And many, if not most, taxes are paid under the compulsion of that threat.The government does not, indeed, waylay a man in a lonely place, spring upon him from the road side, and, holding a pistol to his head, proceed to rifle his pockets. But the robbery is none the less a robbery on that account; and it is far more dastardly and shameful.The highwayman takes solely upon himself the responsibility, danger, and crime of his own act. He does not pretend that he has any rightful claim to your money, or that he intends to use it for your own benefit. He does not pretend to be anything but a robber. He has not acquired impudence enough to profess to be merely a "protector," and that he takes men's money against their will, merely to enable him to "protect" those infatuated travellers, who feel perfectly able to protect themselves, or do not appreciate his peculiar system of protection. He is too sensible a man to make such professions as these. Furthermore, having taken your money, he leaves you, as you wish him to do. He does not persist in following you on the road, against your will; assuming to be your rightful "sovereign," on account of the "protection" he affords you. He does not keep "protecting" you, by commanding you to bow down and serve him; by requiring you to do this, and forbidding you to do that; by robbing you of more money as often as he finds it for his interest or pleasure to do so; and by branding you as a rebel, a traitor, and an enemy to your country, and shooting you down without mercy, if you dispute his authority, or resist his demands. He is too much of a gentleman to be guilty of such impostures, and insults, and villainies as these. In short, he does not, in addition to robbing you, attempt to make you either his dupe or his slave.The proceedings of those robbers and murderers, who call themselves "the government," are directly the opposite of these of the single highwayman.In the first place, they do not, like him, make themselves individually known; or, consequently, take upon themselves personally the responsibility of their acts. On the contrary, they secretly (by secret ballot) designate some one of their number to commit the robbery in their behalf, while they keep themselves practically concealed.

Source: No Treason (1867–1870), No. VI: The Constitution of No Authority, p. 12–13

Context: It is true that the theory of our Constitution is, that all taxes are paid voluntarily; that our government is a mutual insurance company, voluntarily entered into by the people with each other; that each man makes a free and purely voluntary contract with all others who are parties to the Constitution, to pay so much money for so much protection, the same as he does with any other insurance company; and that he is just as free not to be protected, and not to pay any tax, as he is to pay a tax, and be protected.But this theory of our government is wholly different from the practical fact. The fact is that the government, like a highwayman, says to a man: Your money, or your life. And many, if not most, taxes are paid under the compulsion of that threat.The government does not, indeed, waylay a man in a lonely place, spring upon him from the road side, and, holding a pistol to his head, proceed to rifle his pockets. But the robbery is none the less a robbery on that account; and it is far more dastardly and shameful.The highwayman takes solely upon himself the responsibility, danger, and crime of his own act. He does not pretend that he has any rightful claim to your money, or that he intends to use it for your own benefit. He does not pretend to be anything but a robber. He has not acquired impudence enough to profess to be merely a "protector," and that he takes men's money against their will, merely to enable him to "protect" those infatuated travellers, who feel perfectly able to protect themselves, or do not appreciate his peculiar system of protection. He is too sensible a man to make such professions as these. Furthermore, having taken your money, he leaves you, as you wish him to do. He does not persist in following you on the road, against your will; assuming to be your rightful "sovereign," on account of the "protection" he affords you. He does not keep "protecting" you, by commanding you to bow down and serve him; by requiring you to do this, and forbidding you to do that; by robbing you of more money as often as he finds it for his interest or pleasure to do so; and by branding you as a rebel, a traitor, and an enemy to your country, and shooting you down without mercy, if you dispute his authority, or resist his demands. He is too much of a gentleman to be guilty of such impostures, and insults, and villainies as these. In short, he does not, in addition to robbing you, attempt to make you either his dupe or his slave.The proceedings of those robbers and murderers, who call themselves "the government," are directly the opposite of these of the single highwayman.In the first place, they do not, like him, make themselves individually known; or, consequently, take upon themselves personally the responsibility of their acts. On the contrary, they secretly (by secret ballot) designate some one of their number to commit the robbery in their behalf, while they keep themselves practically concealed.

Source: No Treason (1867–1870), No. VI: The Constitution of No Authority, p. 24; the first sentence here is widely paraphrased as: A man is no less a slave because he is allowed to choose a new master once in a term of years.

Context: A man is none the less a slave because he is allowed to choose a new master once in a term of years. Neither are a people any the less slaves because permitted periodically to choose new masters. What makes them slaves is the fact that they now are, and are always hereafter to be, in the hands of men whose power over them is, and always is to be, absolute and irresponsible.

The right of absolute and irresponsible dominion is the right of property, and the right of property is the right of absolute, irresponsible dominion. The two are identical; the one necessarily implying the other. Neither can exist without the other. If, therefore, Congress have that absolute and irresponsible lawmaking power, which the Constitution — according to their interpretation of it — gives them, it can only be because they own us as property. If they own us as property, they are our masters, and their will is our law. If they do not own us as property, they are not our masters, and their will, as such, is of no authority over us.

But these men who claim and exercise this absolute and irresponsible dominion over us, dare not be consistent, and claim either to be our masters, or to own us as property. They say they are only our servants, agents, attorneys, and representatives. But this declaration involves an absurdity, a contradiction. No man can be my servant, agent, attorney, or representative, and be, at the same time, uncontrollable by me, and irresponsible to me for his acts. It is of no importance that I appointed him, and put all power in his hands. If I made him uncontrollable by me, and irresponsible to me, he is no longer my servant, agent, attorney, or representative. If I gave him absolute, irresponsible power over my property, I gave him the property. If I gave him absolute, irresponsible power over myself, I made him my master, and gave myself to him as a slave. And it is of no importance whether I called him master or servant, agent or owner. The only question is, what power did I put into his hands? Was it an absolute and irresponsible one? or a limited and responsible one?

Source: No Treason (1867–1870), No. VI: The Constitution of No Authority, p. 16–17

No Treason (1867–1870), No. VI: The Constitution of No Authority

Source: No Treason (1867–1870), No. I, p. 7

Source: No Treason (1867–1870), No. VI: The Constitution of No Authority, p. 63, Appendix, last sentence

Section III, p. 7

Natural Law; or The Science of Justice (1882), Chapter I. The Science of Justice.

Section V, p. 13

Natural Law; or The Science of Justice (1882), Chapter II. The Science of Justice (Continued)

No Treason (1867–1870), No. I