„A bűnösökkel szembeni kegyelem kegyetlenség az ártatlanokkal szemben.”

Az erkölcsi érzelmek elmélete (1759)

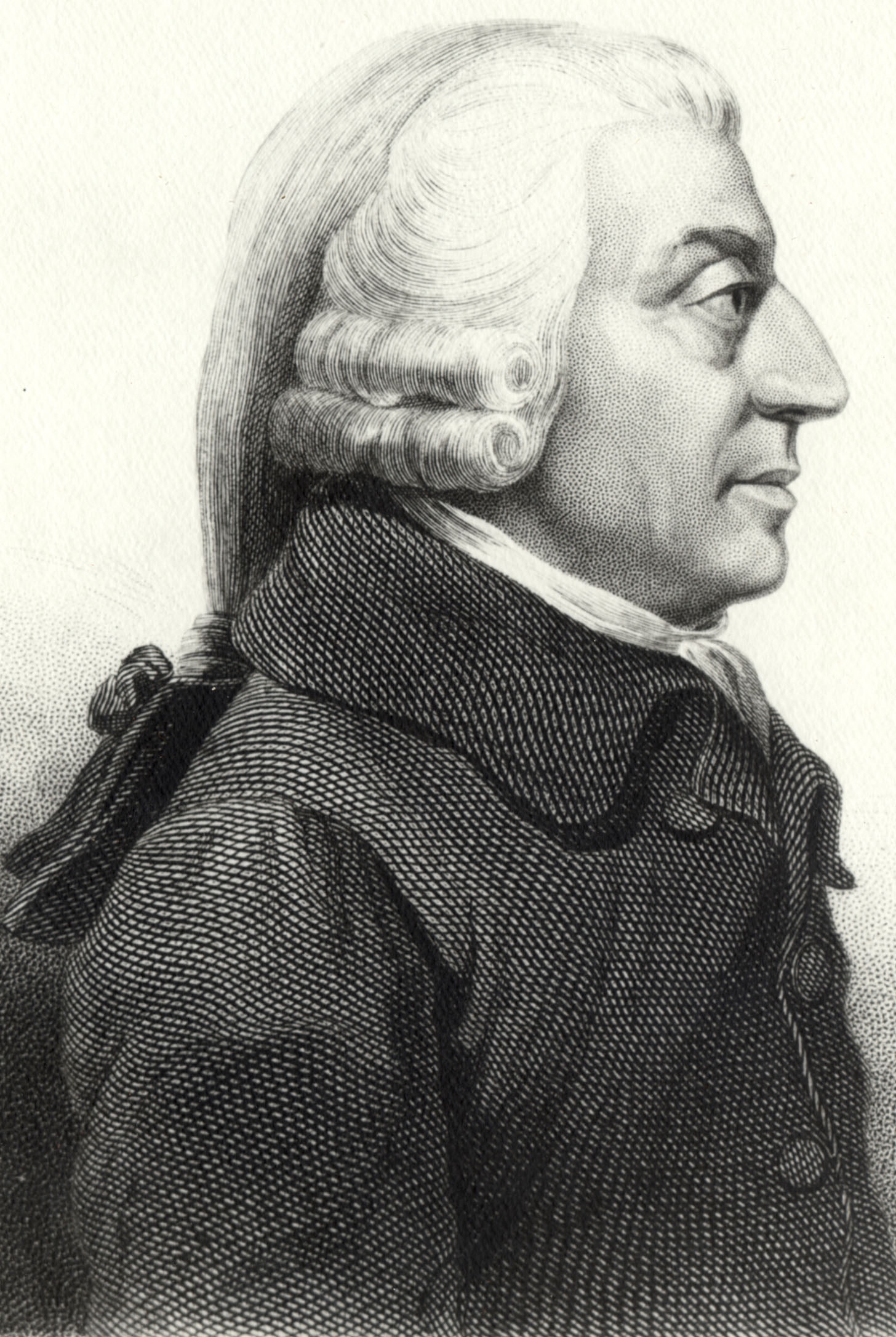

Adam Smith skót klasszikus közgazdász és filozófus. Általában őt tartják a modern közgazdaság-tudomány atyjának. Wikipedia

„A bűnösökkel szembeni kegyelem kegyetlenség az ártatlanokkal szemben.”

Az erkölcsi érzelmek elmélete (1759)

A nemzetek gazdagsága (1776)

Forrás: Második fejezet.

„A tőke szaporodásának a közvetlen oka nem a munka, hanem a takarékosság.”

A nemzetek gazdagsága (1776)

Forrás: Harmadik fejezet.

A nemzetek gazdagsága (1776)

Forrás: Második fejezet.

„Nincs virágzó, boldog társadalom, ahol az emberek többsége nyomorult szegény.”

A nemzetek gazdagsága (1776)

Forrás: Nyolcadik fejezet.

„A gyűlölet és a harag a legnagyobb méreg a jó elme boldogságának.”

Az erkölcsi érzelmek elmélete (1759)

Chap. I.

The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759), Part III

Forrás: (1776), Book III, Chapter IV, p. 456.

Forrás: (1776), Book V, Chapter II, Part II, p. 894.

Forrás: (1776), Book IV, Chapter II

“II. The tax which each individual is bound to pay ought to be certain, and not arbitrary.”

Forrás: (1776), Book V, Chapter II, Part II, p. 892.

“All registers which, it is acknowledged, ought to be kept secret, ought certainly never to exist.”

Forrás: (1776), Book V, Chapter II, Part II, Appendix to Articles I and II, p. 935.

Section II, Chap. I.

The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759), Part VII

Forrás: (1776), Book I, Chapter VIII, p. 87.

Section I, Chap. V.

The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759), Part I

Section I, Chap. III.

The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759), Part I

Forrás: The Wealth of Nations (1776), Book IV, Chapter II

Chap. I.

The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759), Part IV

Section II, Chap. I.

The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759), Part VI

Forrás: (1776), Book I, Chapter I

“the competition of the poor takes away from the reward of the rich.”

Forrás: (1776), Book I, Chapter X, Part II, p. 154.

Forrás: (1776), Book II, Chapter III, p. 381.

“All money is a matter of belief.”

https://www.amazon.com/All-money-matter-belief-quotes/dp/B01M0HLG6B

Attributed

Section II, Chap. II.

The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759), Part II

“Corn is a necessary, silver is only a superfluity.”

Forrás: (1776), Book I, Chapter XI, Part III, (First Period) p. 223.

Forrás: (1776), Book V, Chapter III, Part V, p. 1032 (Last Page).

Chap. I.

The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759), Part IV

Forrás: (1776), Book I, Chapter V, p. 50.

Forrás: (1776), Book I, Chapter XI, Part III, (Conclusion..) p. 282.

Chap. III.

The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759), Part III

Forrás: (1776), Book IV, Chapter III, Part II, p. 530.

Section II, Chap. I.

The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759), Part II

Forrás: (1776), Book IV, Chapter V, p. 563.